Vasudhendra’s Chronicles: From Sandur’s Greens to Literary Triumphs

In 1936, Mahatma Gandhi had been besotted by the post-monsoon greens of Sandur in Bellary. And affixed it with a touristy descriptor: “See Sandur in September.” Vasudhendra, the widely feted Kannada author of Mohanaswamy, Tejo-Tunghabhadra and many other wildly popular works, grew up in that verdant Sandur. In the late 1960s and through the 1970s, mining activities weren’t widespread yet. The small town and its surrounding villages were nested in a landscape contoured by grassy valleys, deep gorges and gushing rivers.

Vasudhendra’s father was a clerk at a mining company and earned, like many employees at that time, a meagre salary. While life at home was relatively austere, the writer did not grow up thinking of himself as “poor.” After all, everyone around seemed equally constrained. The sprinkling of rich folks in the town did not mingle with families of their ilk. While the household always seemed to have enough to eat, money ran dry by the end of the month.

Nurturing Typist Ambitions

Since attending the fee-paying English-medium convent was out of bounds, all three children – Vasudhendra and his two older sisters – were dispatched to the Kannada-medium Government School. There were times in his life, when he berated his father for later-life struggles in English-speaking realms. But such anger was to morph into gratitude when he appreciated a hidden gift: an ability to express himself in a language that tapped into his deepest emotions.

At home, his mother who had a distinct flair for languages, was equally conversant in Kannada and Telugu. Reared in the larger city of Bellary, she had attended a Telugu-medium school. With both parents having studied up to the 10th Standard – a rare achievement then – they aspired for their kids to study further. They hoped especially that Vasudhendra would finish his degree and apply for a typist’s position. He even attended a typing institute and passed the junior and senior levels. Gratefully, he observes that he’s a very speedy typist today.

Amma’s Unfiltered Tales

His father was a quiet, retiring, almost saintly person. So good that Vasudhendra could hardly feature him in his stories. “Good people are boring,” laughs the writer. Not so, with Amma, who despite being a homemaker in a decidedly patriarchal time, was always colorful. For one thing, she was a voracious reader. Family members brought her Telugu books from the public library, each of which she lapped up. She also subscribed to a magazine.

And was like many others, she was crazy about films. After watching the weekly film, blared inside the town’s sole theatre by a clunky old-fashioned projector, she would unfailingly relay the story to her wide-eyed kids. And maybe even to neighbors’ kids, since their tiny homes were built in such proximity. Sleeping outdoors, as they often did on breezy verandahs or tiny porches, ensured their voices overlapped like Venn Diagrams.

Vasudhendra noticed something else. When Amma started telling stories, listeners were rapt. She didn’t bother with censoring her content. Even if there was a rape in a film story, she would say something like: “And then he spoiled her.” The kids sensed something bad had unfolded and that was enough.

Her stories weren’t just fed by books and films. They also drew from life, billowing from tiny incidents that might have felt trivial to others. Like she would travel to Bellary for a day and return with a week full of stories. As Vasudhendra recalls, every leg of her trip was imbued with drama. “On the auto-rickshaw this happened, on the bus that happened, and at home, you won’t believe…” She had an impish sense of humor too. Many years later, when his father passed away, Amma made a statement that cracked up Vasudhendra and his sisters. “At least,” she said, “we had finished watching our Telugu serial.”

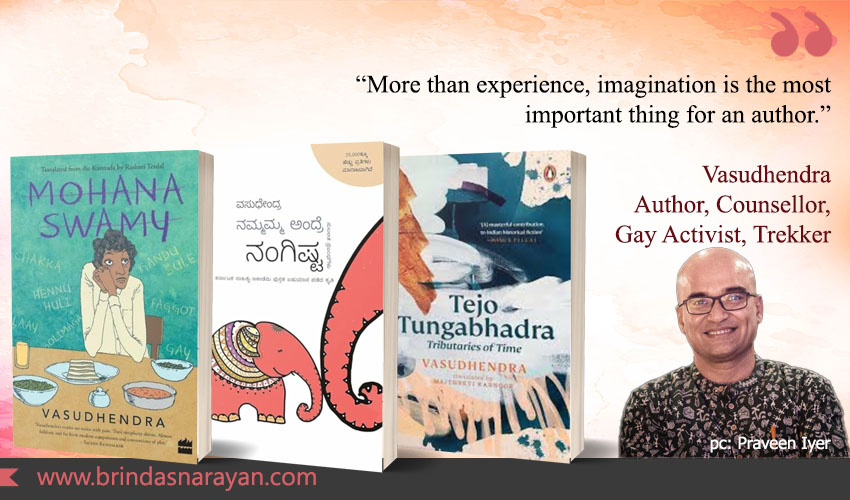

His Amma featured as a key figure in his essay collection titled Nammamma Andre Nangishta. The book sold more than 25,000 copies in Kannada. Vasudhendra recounts how many readers call him, teary-eyed, about the stories resonating with their own experiences. He views the book as a form of shraddha, the remembrance ceremonies that Hindus perform for dead ancestors.

A Math and Science Whiz

When it came to college admissions, Vasudhendra – who had always been an academic star at school – garnered a very high rank in the CET exam. Despite his father being wracked by self-doubt about affording the fees, the family was goaded by well-wishers to take the chance. Landing at NIT-Karnataka, Vasudhendra was stymied by his English or Hindi-speaking peers. To add to this, he contended with masking his sexuality. His bewildering encounters with other closet-gays have been sensitively evoked in Mohanaswamy, a book penned many years later.

Ink and Isolation: Becoming A Writer

On later graduating from the Indian Institute of Science with a Master’s, he entered the IT industry. Poverty and financial distress were banished. But in three years, he contended with a new problem: he was bored by routine work. By then, his sexuality was isolating him. Friends and peers seemed to be moving on: acquiring wives, begetting children. He was not yet brave enough to emerge from the closet.

In 1998, he moved to England on work and felt lonelier. Work ended at 5:30 pm, and he returned home alone. He was not yet adept at reading English, a language that still intimidated him. But he zealously watched international films, borrowing tapes from British libraries, playing them on a low-cost, rented player. Watching hundreds of films, he deconstructed plot, character, narrative style, dialogues, the merging of multiple story lines.

Desperately plumbing for an identity, he picked up his pen and started writing. While that decision might feel fortuitous in retrospect, nothing was clear-cut then. All he felt was a gnawing desire to tell stories, similar to books he had read as a child. Kannada still flowed through his veins, linking his now and then with comforting, phonetic symbols.

In those four or five years in the UK, he wrote every day. He wrote without inhibitions or the self-consciousness that might shadow reputed writers. His lines poured out from his heart. But he didn’t know other writers. Harboring the jittery insecurities of a newbie, he looked for author addresses. And sent out his material, pleading for feedback. Many encouraged him. Jayant Kaikini, author of No Presents Please and a Karnataka Sahitya Academy winner, said: “You write very well, you should write more.” All he needed was that: slivers of recognition from a master.

Triumphing With DIY Publishing

Soon, he had churned out material worth three books. He had also published stories in newspapers and magazines by then, so he attracted reader appreciation. But getting a publisher seemed impossible.

He sent his manuscripts out to nearly 50 people and most did not respond. Only two reverted with polite rejects. A journalist friend, who worked at a Kannada newspaper, said he could cobble a book together: “Rather than struggling so much, why don’t you just do it yourself?”

Vasudhendra was hesitant. Publishing his own book felt like an insult. It seemed to confirm that his material was not worthwhile. Eventually, he decided to give it a shot. After all, it wasn’t that expensive. It cost only 20,000 INR. By then, he had earned enough to cover the costs. But he still worried about sales.

Surprisingly, all 500 copies were sold out within three or four months. Bookshops demanded reprints. Even if publishers had scorned him, readers had voted with their wallets. Since he still did not have a big-name publisher on board, he started his own publishing venture – Chanda Pustaka. Recognizing that many first-time authors would struggle to get their books out, he resolved to champion their voices. Still running as a successful business, Chanda Pustaka, established on January 26th 2004, fosters young writers and debut authors.

So far, Chanda Pustaka has published about 50 authors and 100 books, of which 15 have been penned by Vasudhendra. His authors have even won the Yuva Puraskar award from the Central Sahitya Akademi four times. The publication wields considerable heft in the Kannada literary world, so he contends with a huge spate of submissions, and a long queue of nail-biting authors.

Supporting Gay Lives As A Counsellor

By then, he was back in Bangalore for good. Besides, he was also independent by now. He had earned enough to fund his relatively spartan lifestyle. “I live like a lotus eater,” he says.

In addition, Vasudhendra is also a counsellor. He even qualified himself with a one-year counselling course at Parivarthan. When he faced issues with his own sexuality, he needed to visit counsellors himself. And realized that not many were sensitized to the particularities of being homosexual in India, especially for those from middle or lower-income milieus.

He observes that the suicidal rate is very high inside the gay community. Having registered as a counsellor at Good As You, an LGBT support group, he receives calls from all over the world: Singapore, Australia or even Manipur. Many deal with similar issues: fear of coming out, of not being able to tell wives, separation from a partner. “If you are a gay man and you are separated, neither the legal system, nor your parents or friends worry. You are all alone.”

Sassy Strides: A Playful Midlife Pivot

Till about 34 or 35, Vasudhendra had never played sports. He says many gay boys and men are excluded from sports, because they are afraid of being teased: about an effeminate walk, girly gestures and so on. “Nobody allows you to be part of their team because they think that you walk like a girl, you throw a ball like a girl, you talk like a girl…”

At 35, when he had gained enough confidence in himself, and was unafraid to flaunt his body in courts, he realized he was actually very good at sports. He started playing squash at his apartment and relished the game. At this stage, even if someone laughed at the sway in his walk, or at the way he held a racket, he was unconcerned.

He also discovered a love for hiking. He sought hiking groups by scanning newspaper ads. And turned, soon enough, into an expert hiker. He has climbed Kilimanjaro and Kailash Mansarovar, a strenuous 30-day, 280 kms trek. And heads every year to the Himalayas.

He notes that when you meet the hiking crowd, they only care about where else you have hiked: “They don’t care about real estate prices in Bangalore.” He finds it refreshing to meet an interest group that links your identity to treks completed rather than to some material dimension.

The Ink Never Dries

While allotting time for other activities, Vasudhendra is clear about his priority: writing new books. After all, he’s most content when writing.

To keep his brain fueled with ideas, he reads every day. A lot of nonfiction too. He observes that Satyajit Ray filled his stories with all kinds of trivia. “He knew about birds, animals, science, astrology, psychology.” He strongly urges those who want to write to read widely and indiscriminately.

After Tejo-Tungabhadra, his latest work, he’s writing a book set in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and China. Some parts of a story are set in a forest, and he’s never lived in one. But that doesn’t faze him. His imagination is a superpower, enabling his entry into other minds, times and spaces.

Every book he publishes these days becomes a bestseller in a few months. He wields that kind of reputation among readers. “I’m a big seller, I have that luck,” he says. He has also won the Karnataka Sahitya Academy award twice. And received numerous other accolades.

At 55, he doesn’t see himself stopping ever. He will always be a writer, till his last days on the planet.

References