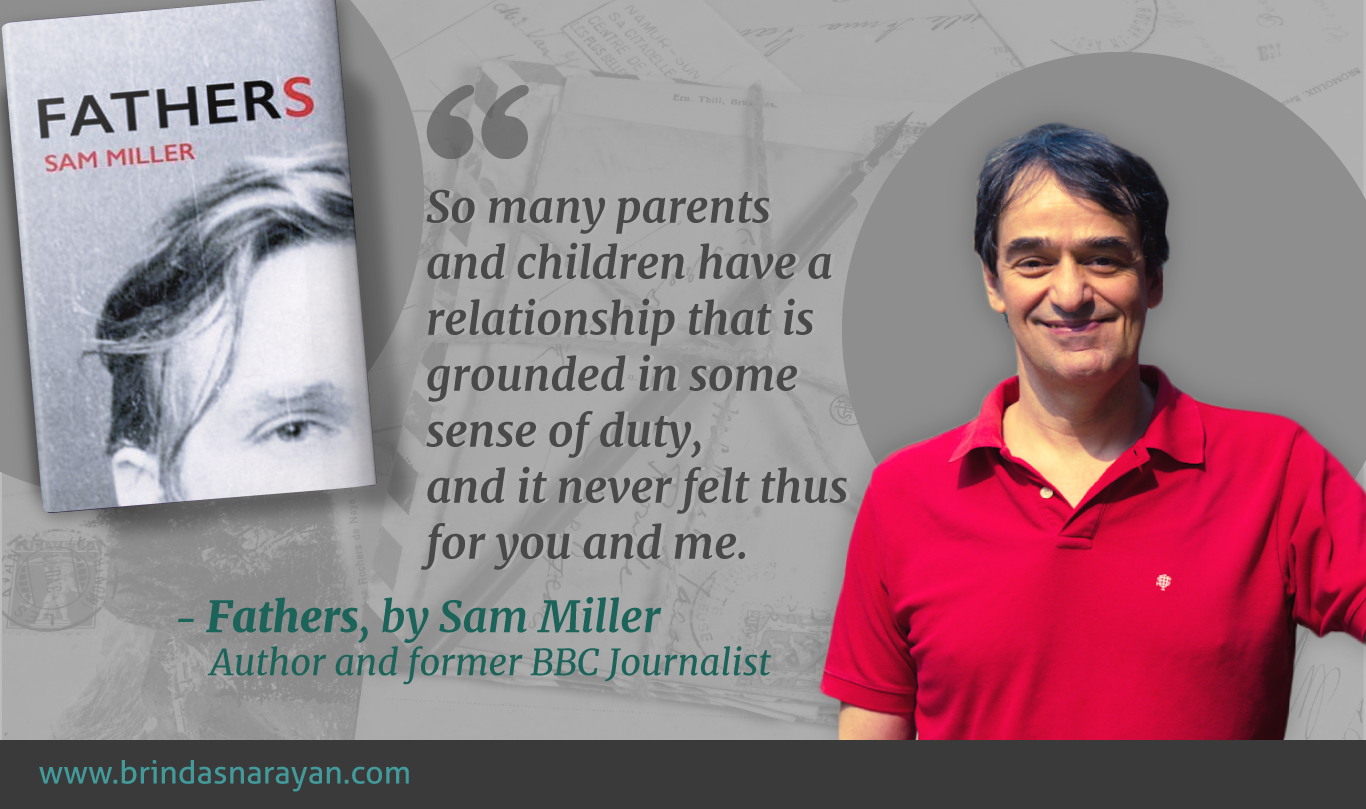

Lessons from a Memoir: Sam Miller Explores Fatherhood, Friendship and Love

While motherhood has often been the subject of social, psychological and cultural studies, fatherhood has received relatively scanter attention. Such diminution of the paternal role affects not only fathers, but also mothers, who are then assumed to be primary caregivers or at least expected to play a more central parenting function.

In Fatherneed: Why Father Care is as Essential as Mother Care for Your Child, the Yale child psychiatrist, Dr. Karl Pruett, observes that fathering is distinct from mothering, and not necessarily in terms of being less nurturing or less responsible for the child’s well-being. Broadly, “fathers” (who, of course, could be women in same-sex couples) are expected to rough-house with kids, and expose them to a greater degree of frustration than mothers are usually willing to subject them to. The tumbles and teasing that accompany such horsing around extend the limits of a child’s world, gradually bracing kids for the strife they are likely to encounter as adults.

Beyond psychological takes, literature and memoirs expand our notions of how “fathers” shape and can be shaped by their children. In Fathers, his stirring, beautifully constructed account of his own relationship with his father, Sam Miller journeys into the past, delving into letters, papers, ticket stubs, photographs, diaries and memories. This trip into kinship ties, the surprises and secrets that marked his growing years, was triggered by Karl Miller’s death on 24th September 2014. Though Karl had always predicted that he would die at any point, he was, as Sam calls it, “a literary hypochondriac.” Displaying a wry and witty self-awareness, Karl had composed the following ditty about himself:

“No poor soul was ever iller

Than Karl Fergus Connor Miller.”

Though the obituary tributes that described him as the “founder of the London Review of Books” or as one of “the last great Bloomsbury men,” were adulatory and accurate, Sam knew that the man could hardly be summed up in those pithy lines.

Till then, Sam Miller, who had written funny, piercing chronicles of his skirmishes and encounters with Delhi and other parts of India, hadn’t consciously sifted through his own childhood. Writing this then, almost as a process of self-discovery or self-construction, he sucks us in nonetheless, redrawing our own cultural maps of what really constitutes “fatherhood”. Or more significantly, reveals the fuzziness embedded in words like “real”.

Karl Miller’s Remarkable Rise from an Orphan to a Literary Arbiter

Raised by his maternal grandmother, Karl Miller described himself as an orphan, since his parents were separated and had never lived with him. Only occasionally encountering his bookkeeper mother in childhood, later in life, Karl would meet frequently with his impoverished painter father – a man who seemed strikingly content with little and also unmoved by material gains and losses.

Karl was conscious about not being like his own parents. He wanted a family, who lived with him, and he wanted friends. But he was also afraid of cultivating such dependence, with all the uncertainties and alterations that relationships inevitably entail. As Sam puts it, “My father chose to enter the world of dependence: the world of success and failure, of connections and fame, of reputation and dissimulation.”

Coming from such a poor family, Karl grew up with very few material possessions. But his home had, strangely enough, “books and newspapers, paper and pencils.” More than anything else, both his working-class parents were also readers – reading Proust, Nietzsche and Dostoyevsky. Later at college, Karl was astonished that people in “higher” classes also read books. He had assumed that reading was a pastime of the poor, of folks who could not afford to be riding horses, doodling or doing whatever else the glamorous set did.

He joined Cambridge, and unlike Sam, who headed there later and hated it, Karl cherished his time at University. He always had a flair for words, and for writing “libelous verses,” often targeted at those in his intimate circles or at enemies. He would use this gift to chaff at his own kids. For instance, Sam Miller was called “Sam Mullah” or “Saddam Miller” when he journeyed to the Middle East to learn Arabic.

From Cambridge, Karl journeyed to Harvard on a scholarship, but was less happy there. He was no longer as much in love with the Ivory Tower life as he had once been. Soon, he opted out of his academic sojourn and embarked on an American road trip with his wife, Jane, and some Cambridge friends who joined them. In 1956, Sam’s parents returned to London. After desultory stints at the Treasury and BBC Current Affairs, Karl became the literary editor at the Spectator. “The orphan boy from a Scottish mining village had become an arbiter of London literary taste at the age of twenty-six.”

Moving from the Spectator to other magazines, and eventually stitching together a career filled with rich reading and writerly experiences that launched many of Britain’s memorable authors and poets including Philip Larkin, Clive James and Seamus Heaney, Karl Miller also fulfilled another promise to himself. Of staying staunchly involved with his three children, often ferrying them to football games with ex-college friends or otherwise “rough-housing” with them, engaging in “ribald” jokes or teasing, cultivating their own literary sensibilities with poetry readings and clubby conversations. He also read and edited all of Sam’s writing, subjecting them to the careful scrutiny and incisiveness of his magazine pieces.

Sam Miller Encounters a Family Secret

And then in Part Two of the book, Sam Miller reveals a secret that he had been told when he turned fifteen. His mother disclosed that his father, at least in biological terms, wasn’t Karl Miller but Tony White, one of Karl’s friends from Cambridge. Jane and Tony had embarked on an affair while holidaying in Rome, culminating much later, in a pregnancy.

Tony, whom Sam starts studying through various letters and documents, had emerged from a more conventional, middle-class upbringing, and grew up to be “determined and contrary.” Starting out as a “romantic actor” at Cambridge, he soon abandoned the theatre and tried his hand at a host of unconventional jobs like lamp lighting (in the days, when street gas lamps needed to be lit by a long steel rod), grape picking and driving delivery vans. He was also a ghostwriter and translator, transitioning with “princely panache” between the brain and the brawn. (Karl called him the “the Prince of Panache”.)

The charismatic Tony, who died rather early and too suddenly for his friends, hadn’t achieved the social distinction of Karl. But nonetheless, he garnered a host of paeans at his demise. Even if his achievements weren’t impressive, his life had left a deep imprint on the people around him.

Charting the differences between Tony and Karl, the former definitely more of an explorer, more bohemian and perhaps even somewhat of a drifter, with the latter, more rooted, and seemingly stolid, Sam, in a tone that veers between affection and dispassion, narrates the sequence that led to his own birth, the bewilderment that followed his mother’s announcement, and through it all, his own unchanged relationship with Karl. Of course, Tony had died rather early at 45, so Sam never met with him as a possible “father.” But even after exploring all the “what ifs” – What if Tony had lived, for instance – Sam is clear about his own filial loyalties: “And there was no doubt in my filial mind, then and now: Karl Miller was, is, always will be my father. Tony White was a half-forgotten secret.”

The title page of Silas Marner, one of the well-known classical takes on how parenting can change a man, carries a poem by William Wordsworth: “A child more than all other gifts that earth can offer to a declining man brings hope with it and forward-looking thoughts.” In the book, George Eliot shows us how a man, who is not the biological father of his child, can be changed by his relationship with a child whom he nurtures and protects as his own. In a style that is reminiscent of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, Sam Miller affirms Eliot’s take with tenderness and precision, but without the “winsomeness” that his father Karl Miller abhorred in prose.

References:

Miller, Sam, Fathers, Penguin Random House, London, 2017

Pruett, Karl D., Fatherneed: Why Father Care is as Essential as Mother Care for Your Child, Broadway Books, New York, 2000