The Making of An Artist

Shanthamani Muddaiah is a highly-regarded, Bangalore-based artist whose works feature in local, national and international collections. Her creations are showcased by a range of collectors, including but not limited to Swiss Re (Bangalore), RMZ (Bangalore), Abishek Poddar (Bangalore), Jindal Collection (Delhi), C-Collection (Switzerland), Collection Helene Lamarque (Miami), and Phillips de Pury Collection (New York). As well as by private collections situated in Cologne and Luxembourg.

Growing Up Into A Feisty Teenager

Shanthamani’s parents emerged from agrarian families, with her father being the first to migrate to the city and garner a government job. As first-generation urban-dwellers, Muddaiah, her brothers and a sister flitted between their school lives in Mysore and their extended family in the village.

But despite migrating from their village, her parents hadn’t relinquished its norms. Especially not for women. Since her father worked as a typist in the Education Department, schooling was ensured for all the children. There was, however, a sense that Shanthamani’s life would assume a different trajectory from that of her brothers and a sisiter.

Her parents weren’t necessarily shunning the values of others around them. After all, their daughter was born in the late 1960s. At a time, when even among the majority in the nation, the status of women was unquestionably precarious. This despite Indira Gandhi helming the country’s then most powerful party. “It didn’t mean that all women had that kind of opportunity or vision of leadership for themselves,” Muddaiah says.

During summers spent in her village, near Pandavapur in the Mandya district, Shanthamani encountered a different kind of future experienced by young girls. Who had been typically married off at 12 or 14 years old, who bore kids too soon, and who then suffocated inside unrelenting patriarchal strictures. The artist herself was only an infant, like five-years-old when she first started hearing about bodies floating inside the village canal. That’s where some hurled themselves, as victims of child-marriage, domestic abuse, teenage pregnancies or throttling ennui.

Over time, she bonded with many village girls. Who often looked up to her, as the worldly city dweller. Even as they slathered her with affection and questions, she would watch them morph over visits. From nimble hopscotchers to wives and mothers, tethered to husbands and infants, their playtime and outdoor forays excised by ancient practices.

In the meanwhile, at home, her parents intended to get her married early too. To a husband of her their choosing. To a lifetime of domestic confinement, on a path similar to her mother’s, and other women around her. She started looking at her own body askance. Wondering why she had been born that way, why she was female when all the perks seemed awarded to males.

But she had also witnessed other women. Like some of her aunts, who had been widowed during the time of the Freedom Movement. Who, despite losing their husbands in a society that degraded widows, were resilient and gutsy. And who seemed to live with an enviable brio.

Shanthamani started realizing that she could be different. After all, there was this questioning, feisty voice inside her. “I had seen things that happened to women and I wondered why I should be that way? Why does no one listen to me?” Making the most of her schooling, she resolutely set out to an art college in Mysore.

Discovering Her Passion for Art

Though her entry into the Chamarajendra Govt. College of Visual Arts (CAVA) was straightforward, her time inside was marked by challenges. While she had practiced many traditional crafts as a child, she didn’t stem from a household that knew much about art or painting.

On her first day at CAVA, she confronted tubes of paint for the first time. Unlike many of her fellow-students, she did not know how to puncture a hole in the tube, to squeeze the colourful pigments out.

Moreover, by the third year, she was the only woman in a batch of sixteen students, though she did have other women to interact with at college. Marking herself out as a “rebel” – after all, there was no other woman artist in her family or circle – at first, she imitated boys. “I tried to behave like these town boys, so I did everything that they did.” Later, she recognizes this as an identity crisis of sorts. Like many young adults, she too was trying to find herself. Fortunately, for her, she really took to art. In those five years, she not only absorbed lessons in painting and art history, she also found her ikigai.

On graduating from CAVA, she wished to head to The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda (MSU, Baroda), one of the nation’s premier art institutes. MSU and Shanti Niketan were the only colleges in the country, at that point, that awarded Master’s Degrees in the Fine Arts. The competition was stiff. Nearly 70% of the seats were reserved for Gujaratis, while others were earmarked for other nationalities.

Meeting Intrepid Women at MSU

Drawing on the fierce determination that had foiled her family’s plans, she won her admission to MSU and thrived inside its multicultural environs. In the new terrain, she was galvanized by female role models. Because of Gandhi’s insistence on prioritizing women’s education, Gujarati women had free rides into schools and colleges.

For the first time, Shanthamani met women who were as resolute about their careers, as they were about other aspirations. Some were doctoral scholars, others were teachers or professors. “This really changed me because I hadn’t seen women with that kind of space or power. Until then, most women I met were homemakers.”

She also grasped that in such a space, one’s past baggage – whether rich or poor, runaway or homebound – mattered less than the plans one forged. Very quickly, she gleaned the need to carve her own path. She also befriended women from previous and later batches. Connections forged there have stayed with her, serving as lifelong emotional anchors.

Emerging As a Sculptor

At first, Muddaiah had trained herself as a painter. While painting, she discovered that she did not enjoy working with delicate brushes, stroke by feathery stroke. Rather, she was a very tactile person. She enjoyed the physicality of painting. Maybe this arose from her outdoorsy rural romps and tomboy instincts. “I wanted to kind of load pigments onto the surface. It was a sculptural approach rather than a painterly approach.”

It took her a while to grasp that she enjoyed sculpting more than painting. Even today, her rigorous painterly training enables her to articulate her sculptural forms on paper, with paints, before translating them into vivid 3-dimensional works.

But the rough-housing that goes into building her sculptures is also diffused by a contradictory impulse: to depict femininity, with its fragility and power. Recalling female relatives who toiled as farmers, she tries to evoke their quiet strength, resilience and vulnerability. It was also a form of female power that diverged from city stereotypes during the 1970s: which primarily comprised “nail-painted stenographers, typists, nurses and at the top of the pyramid, gynaecologists.”

Drawing again from her rural past, Shanthamani discloses that for her, daintiness was never a part of the feminine. Even as she continued experimenting with paints, she had started mixing newspaper with colour, deliberately turning it messy and forging it into a paste. She used this coloured paper to layer her surfaces.

Learning Paper Making at Scotland

As she was working on such pieces, she found that she wanted to understand paper better. To divine the depths of a seemingly surface material. To do this, she was awarded a Charles Wallace fellowship to travel to Scotland to study paper making in artistic practices and paper pulp production.

She also started viewing paper differently. It was no longer a medium on which one could paint or layer texture, but also a material that could be forged into 3-dimensional structures.

Integrating Community Voices

Her time in Scotland had also granted her other insights. For instance, while working inside a studio, she often listened to FM radio on BBC. Topics covered included global warming. Besides awakening her early interest in the earth’s eroding ecology, the program also offered other perspectives. She noticed that the radio wasn’t just a one-sided monologue, with a radio-jockey or narrator hogging the airwaves.

Rather, many members of the community called in, offering their views on various issues. This intrigued Shanthamani. She realized that collective voices could be a power in themselves. For instance, they were protesting the import of genetically-altered maize from America. They were able to halt the import, just by expressing their opinions: “It was amazing to listen to this kind of radio because I was mostly alone in the studio making paper.”

Discovering Possibilities With Carbon

Moreover, her curiosity about carbon and its relationship to global warming had been stoked. When she returned to India with mastery over various paper-making techniques, she toyed with different materials that she could fuse with paper. She played with sandwiching photographs and textiles. And even stitched threads into paper. She happened to mix charcoal with pulp and discovered that it transformed into a completely new kind of material. She sensed, as an artist, that it radiated possibilities.

She started making fragments with paper and charcoal, and slowly pushed boundaries – fusing parts into larger works. All along she played with how far she could push paper, which was, after all, still fragile. But there were ways in which it could be infused with strength. In a process akin to science, she experimented furiously in her studio, ideating, doing, observing results.

Besides, she was using cinder – a waste product generated by burning coal. Though architects have tried to use cinder to fill sunken slabs for toilets on upper floors and for a few other purposes, the wastes generated are too vast to ensure significant reuse. By beautifying the city and other spaces with a waste product, she was making a more layered statement.

She’s also conscious of other associations linked with carbon. Homeless folks might warm themselves over a coal-fired pit, just as the ultra-rich might savour smoky kababs. It’s a working class material, since it evokes images of coal mines. “It’s a mucky, dirty and polluting material, drawn from the earth by hard work.”

But it’s also fundamental to life, the main element in organic substances. Even as she moulds it and reconfigures it, she wonders about how it’s mined, and sometimes shipped out of the country, to power other economies: “What does it mean for India to take out all that coal blast without any regulations, without any compensation for the land that gets gobbled up in its mining?”

Creating The “Backbone”: Exhibited at the Kochi Biennale (2014)

While giving birth to her son, Shanthamani recalled the manner in which the epidural was injected into her spine. Her project “Backbone” exhibited at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2014 reflects both this distinctly feminine experience as well as the ceaseless flow of the River Ganga.

The artist herself traversed the length of the whole river, starting from Allahabad to Farakka, in West Bengal by boat. Then from Kolkata to Gangasagar, and along the upper part of the river, partly by car and partly by trekking along the banks. All along, she documented what she saw, trying to understand why those waters have been such a central idiom in the country. Apart from religious references, she encountered the way in which inhabitants of remote islands were entirely dependent on its ebbs and flows.

Another aspect of the Ganga that struck her, was the river’s abiding presence as well its ceaseless gush. It felt like the source of the nation’s philosophy, embodying ephemerality and impermanence.

Fusing Art With Life and the Self

Muddaiah’s artistic journey has also been one of ongoing self-discovery. Conscious of her inner ferment, and an unwillingness to settle down – especially into a normative female life – she works almost every day.

For her, work, play and life are inseparable, with each realm blurring into the other. Till her son turned 12, she had him doing his homework and school projects inside her home studio. When she felt he was old enough to experience autonomy, she moved her studio out of the home. Very recently, she has moved into a new studio that resembles her idyllic workspace.

Even the process of searching for the self has thrown up discomfiting truths. For instance, she observed that all along in her works, she had often painted herself as a shadow figure. Partially, such invisibility may have been acquired from parental strictures: “Don’t talk while adults are talking.”

She also recalls, as a girl, being asked not to interject or interrupt. The more common phrase was: “Don’t come in the middle.” Her father once used a Kannada phrase – ele marekai – which signified that beautiful fruits were hidden under leaves. She too was expected to stay protected and invisible.

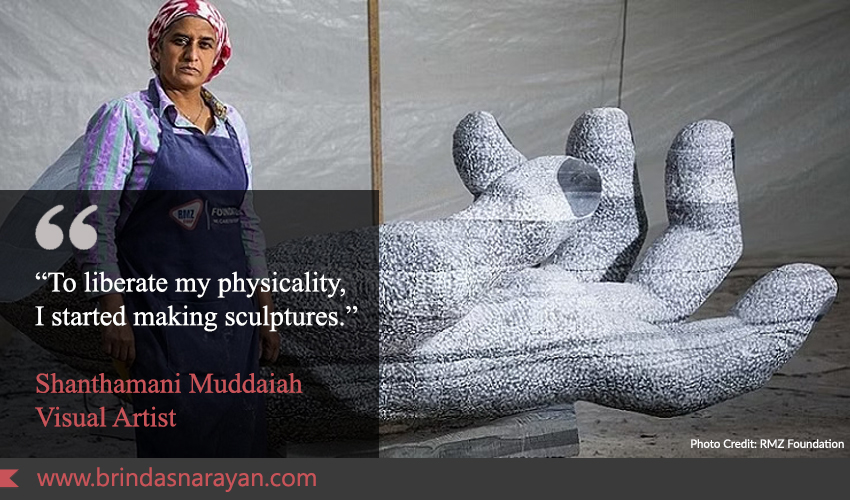

One of the reasons she imbues such strength and muscularity into her figures, is to counter her own feeling of being a quiet, shadowy presence. “To change that, to liberate my physicality, I started making sculptures.” Of course power always fuses with opposites: fragility and vulnerability, emblematic perhaps of all human beings, but particularly of women. Someone commented that her use of red-oxide, which derives from the oxidation of iron, signified a tough material. On the other hand, when iron rusts, it collapses into flakes that can be easily brushed off.

Beautifying Cities

Of late, she has also been installing sculptures in public spaces. Outside the “Do Not Touch” spaces of museums, she’s fascinated by the manner in which viewers can encounter her works in visual and tactile ways. Her public sculptures are currently installed at five or six places in Bangalore: like outside the SAP lab (RMZ) in Whitefield, outside the Ecospace building in Bellandur, by the Swiss Re office at Domlur. One more will be installed soon at the T2 terminal at the Devanahalli airport.

She also has installations in New York and in Gassin (Provence), in the South of France. She strongly feels that public art works strengthen democracy since they enable interactions with people of all types. Moreover, they invite dialogues – which is really what art is about: a dialectic between the artist and viewer, as well as the object and its observer.

Motivating Younger Artists

To younger artists, her advice is to stick with the process, and figure out their own journeys. After all, self-discovery is an ongoing endeavour. She also cautions them to go beyond making money, or garnering recognition. In the end, what really matters is becoming comfortable with oneself and achieving contentment. Besides, no career is easy. She disagrees that artists have it harder than others. Even for folks who want to monetize their talents, she observes that there are many routes, besides the sale of one’s work: like mentoring other artists, conducting workshops, teaching.

Remaking The Nation

She also emphasizes that art is not a peripheral or even optional activity, as many people might presume it to be. It’s central to all cultures, and it’s baked into our identities. It’s not just about creating paintings that hang in galleries, or making pieces that decorate living rooms. Art is woven into all aspects of life, including our cultural sense of self, the conduct of elections, the economy, the celebration of festivals.

Like art, our dresses, our foods, our vocations, our seasons and climates are woven into our sense of self, and displacement or alienation from such identities can create huge psychological and social fissures. While we may not wish to preserve all elements from the past, we have to be conscious of how the aesthetic interacts with our everyday living, so that we consciously preserve some and shed others: “If we are not aware of it, or not ready to debate it, someone else can manipulate it,” Muddaiah says.