An Unsettling Conversation Sparks off a Career Transition

Deepa Purushothaman was elated. She had recently made it to partner at Deloitte, a global professional services firm. And she was celebrating with Walter, a friend from graduate school who had been similarly elevated at his law firm. Even as the waiter filled their glasses with sparkling bubblies, Deepa was dissecting tricky office situations post her promotion. The inevitable tangle of politics that most senior people, and especially women and minorities, navigate. Suddenly Walter, who had been a long-time friend she trusted, said something that stumped her: “You are a ‘twofer.’ You have nothing to worry about. I on the other hand, as a white man, am going to have to work hard to earn what comes next…”

At that moment, Purushothaman did not know what she was feeling. It would take her a while to articulate her disquiet with precision. But she did sense the cheer evaporating, and a familiar confusion taking root.

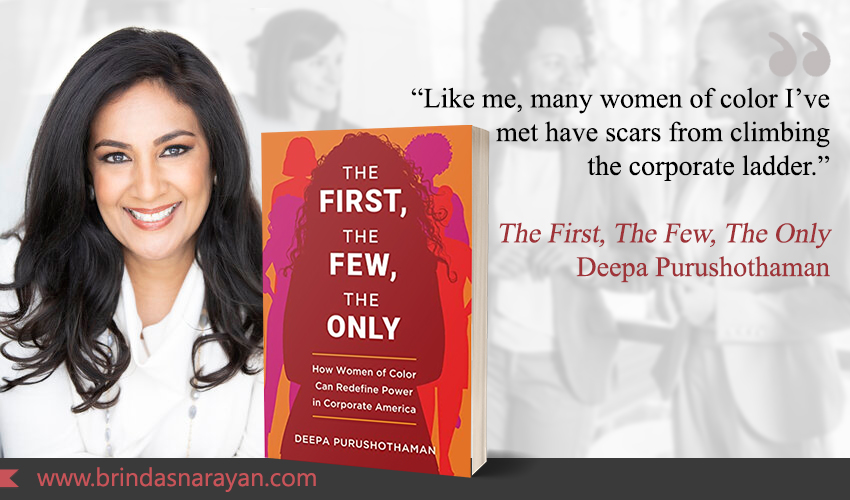

She observes that as a woman of color, it is inevitable to juggle conflicting emotions. Triumphs are frequently accompanied by putdowns or patronizing kudos. What’s worse is that you are often the “first” woman in that team, or at that level, or in the boardroom. Or you are one of the “few”. Or you’re the “only” one. Capturing that sense of isolation, Deepa’s book addresses “The First, The Few and The Only” – Women of Colour (WOC) in American business roles, who have to assure themselves, as the author often did: “you don’t have to see it to be it.”

After that dinner, her friend’s words kept ricocheting inside her head. Deepa was also aware that she had access to exclusive networks. She was one of the youngest and the first Indian woman to make it to consulting partner at Deloitte. Besides consulting with clients, she also ran the Women’s Initiative at Deloitte, fostering an “inclusion strategy” for its more than 100,000 employees in the U.S.

Instead of persisting on her blazing corporate track, she realized that she wanted to leverage her connections and experiences to drive systemic changes. Though abandoning a 20-year-old corporate career was not easy, she redirected her drive into bigger questions. She started conducting research on structural racism at the Women and Public Policy Program at the Harvard Kennedy School. She also started an enterprise, nFormation that helps with leadership coaching and strategic placements of WOC in select positions. She co-founded this with Rha Goddess, founder and CEO of Move The Crowd.

Examining Belief Systems

Contending with your identity might require foraging into the past. Into experiences that shaped your personality.Deepa herself was raised in Whitehouse Station, a predominantly white community in New Jersey. Her mother sent her to school with braids and a bhindi, requiring her to inhabit difference from an early age. This, however, did not imbue her with confidence. Instead, she “internalized the pain and shame of being different, and tried even harder to fit in.” And expectedly, she did not fit into India as well, a place she visited on vacations.

So she assumed that not belonging was part of her DNA. Till her adult years, when she recognized that the external environment was not fixed, but malleable. And wasn’t “fair” to begin with.

Finding Few Role Models

She emphasizes the manner in which top positions – in Fortune 500 companies or in politics or media or in other spheres – have dominantly been held by people who don’t look like her. Not seeing people like you in the echelons of power can exacerbate your inadequacy and self-doubt. Michelle Obama talks eloquently about imposter syndrome in her book, Becoming and at various forums: “For so long, women and girls have been told we don’t belong in the classroom, boardroom, or any room where big decisions are being made. So when we do manage to get into the room, we are still second-guessing ourselves, unsure if we really deserve our seat at the table.”

Recognizing Diversity Among WOC

Purushothaman is keenly aware that WOC comprises diverse and distinct voices. Black experiences might vary widely from Asian ones, and both may have little in common with indigenous women. Even “Black” is an umbrella term that barely stitches together the variegated experiences of African Americans.

Being sensitive to specificities however does not preclude Deepa from identifying common struggles faced by WOC, while climbing corporate America’s ladders. WOC as a term is not meant to supplant identities, but as Professor Efren O. Perez of UCLA puts it, it can be deployed as a “super identity.” The idea being to garner collective power and forge solidarity.

Deepa also uses the word “co-conspirators” for fellow WOC, rather than “allies.” As the author and activist Alicia Garza suggests, “Co-conspiracy is about what we do in action, not just in language.”

Collating Stories To Build A Collective Voice

In her book, Purushothaman has documented stories from WOC at all levels – entry, mid and senior positions. She met women for meals, on the phone, on Zoom. She felt galvanized by her conversations, because she senses that change is afoot. Many WOC reiterated that they “want to alter existing narratives, change the game, and lead in a brand-new landscape.

Her advice to WOC who want to rediscover their own power is driven by the Zulu word, “sawubona”, which means: “I see you; you are important to me and I value you.”

Recognizing Design Flaws in The Workplace

In October 2020, she chatted with Verna Myers, the VP of inclusion strategy at Netflix. Myers pointed out one basic issue with most companies. She said, “Deepa, Corporate America wasn’t designed by women of colour.” For instance, Myers brought up airplane designs. In the 1970s, only 2 to 3% of Boeing engineers were women. If women had possessed a stronger voice then, we wouldn’t have to stand on our toes, hoist our bags over our heads to stow our cabin bags into overhead compartments. Myers recognizes that she herself is an unusually tall woman. But most women are shorter. “And for many of us, upper-body strength is not our strong suit.”

When Myers dwelt on this analogy, Deepa could relate at once. As do many of us, who may not have realized why the design works so well for one gender, and not for another. As Purushothaman says, “Why do I feel like it is my deficit when I can’t put my luggage up high?”

Verna observes that similar systemic flaws are baked into corporate workplaces. Which were largely designed for “white, cis, straight men” and hence feel discomfiting for others. In a Feb 2021 HBR article titled “Stop Telling Women They Have Imposter Syndrome,” author Ruchika Tulshyan and Jodi-Ann Burey reiterate: “Academic institutions and corporations are still mired in the cultural inertia of the good ol’ boys’ clubs and white supremacy.”

Breaking Other Myths

There’s a notion that there just aren’t enough qualified or capable WOC to fill certain positions. But as Deepa points out, “[the] idea that the pipeline is broken” is a myth. It just happens that white male leaders tend to congregate with other white males, and are hence prone to looking in the wrong spaces.

Moreover, there is a sense that like attracts like. Leaders pick people that feel familiar. As an example, Purushothaman cites a story from Lyn, a Chinese American partner at a top firm. Lyn worked with Janet, a brilliant Singaporean woman, who Lyn thought was very capable. However, in an honest one-on-one, Lyn’s mentor David mentioned that Janet’s English was too heavily-accented and might stymie her rise. Lyn advised Janet to move to Japan, where she soon made partner. But later, Lyn started questioning the manner in which the differently accented were being overlooked in the U.S.

In a McKinsey and LeanIn.Org study titled, “Women in the Workplace 2020” white women and WOC comprised 50% of the entry-level workforce. But at the C-Suite levels, both tapered off. However, the paring down was not uniform, since “six times as many white women ended up in that C-Suite as women of colour.”

Why are WOC dropping out? As Purushothaman points out, it’s statements like “You need to dress more professionally. Don’t wear your hair that way.” Or “you are being too loud. Don’t be so emotional and excitable.” These statements pass a message to WOC: you don’t fit in.

The much touted value of authenticity or being yourself works against WOC. A popular resume study by Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan (2003) dispatched resumes in response to help-wanted ads in two major American cities. “They found a white name yielded as many callbacks as an additional eight years’ experience from a person of colour.” This was reinforced by another study (2016), titled “Whitened Resumes: Race and Self-Presentation in the Labor Market,” which also established that “whitening” resumes had payoffs. They resulted in many more callbacks.

While The First, The Few, The Only alerts WOC to the fact that they’re not alone and offers strategies to bolster their personal and collective power, policymakers and leaders can glean suggestions to shift the zeitgeist.

References

Deepa Purushothaman, The First, The Few, The Only, HarperCollins Publishers, 2022

https://www.vogue.com/article/michelle-obama-interview-empowering-young-women