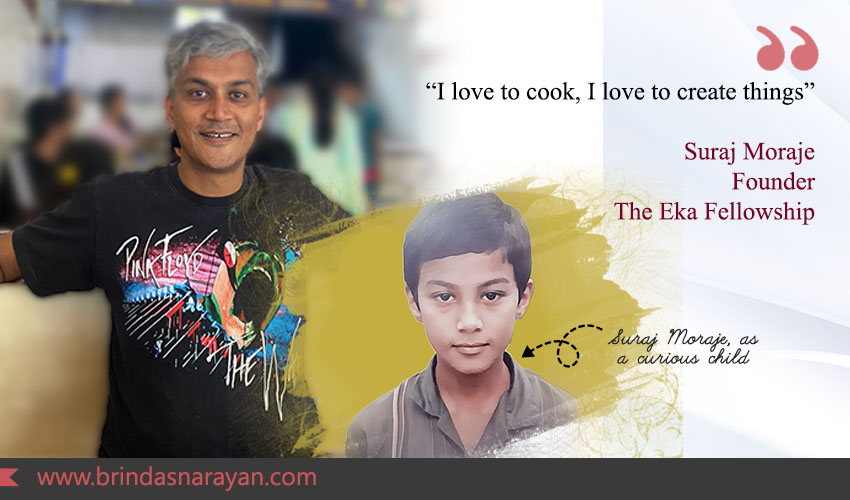

Cooking, Consulting and Change-Making: A Life Story

Flipping Pans and Pages

Suraj Moraje cooks every day. Sometimes, pasta made from scratch, the flour and salt combined with eggs, the dough kneaded and patted aside, partitioned, thinned out, and scissored into strips. Multitasking comes easily to the ex-Quess Corp CEO and McKinsey Senior Partner. While the strips boil, cubed tomatoes and diced onions are sautéed with fresh basil and oregano till the sauce bubbles into a perfect tang. On other days, he dishes out his Mangalorean favorites, like sweet-sour majige huli with sliced cucumber. His sons, both teenagers now, take it for granted that Daddy cooks, as they should, in households that no longer subscribe to outdated gender relations.

Besides cooking, Moraje gardens. With a very hands-on approach that involves getting soil under his fingernails. Dispensing with the need for a maali, he weeds, tills, digs, sows seeds, plants saplings, mixes in manure, clips leaves or mows the grass, and trims hedges. All this with the fussy attentiveness of a parent who knows what it takes to cultivate anything.

Being hands-on, rooted, grounded, doing things himself was woven into his middle-class ethos. As a child born in Tanzania – the East African country that bedazzles with lakes and wildlife parks – and raised in Zambia, he was accustomed to being a misfit. For one thing, as an Indian, he was already an outsider. His foreignness was saddled with another oddity when he received a double promotion from the 2nd Standard to the 4th Standard. As a result, he was both younger and punier than his peers. So he shied away from sports, afraid of being outdone by bulkier footballers and towering athletes. And took to books, chomping through pages that spirited him into other worlds. It’s a habit that stayed with him, even as he navigated other transitions.

Sunny Spaces and Choices

Looking back, he has mostly happy memories of those years. He recalls “lots of sun, lots of open spaces”. In the 8th Standard, he was sent to a boarding school in Bangalore. At Bethany’s – the school he was admitted to – he was regarded as strange by fellow students. For one thing, he knew nothing about cricket. Moreover, “people thought I was crazy to go to a park and read a book.”

He still doesn’t know how the thought was sparked but he does recall wanting to be an engineer. Maybe, as he puts it, he absorbed the social memes of that era. Besides, there was the parental expectation, planted by his Physics school teacher father, that he would earn as much as he could to support a future family. Even now, he marvels at how masculinity, in those days, was defined in rigid terms: that one had to be the breadwinner, prop up the family, and bolster one’s reputation. The kind of expectations that inevitably narrowed choices on what one could strive for.

Navigating Plagues and Possibilities

Bucking the trend, he wasn’t particularly studious during the 11th and 12th Standards. Yet he did well enough on the Engineering Entrance exams to make it to REC, Surat (currently SVNIT, Surat). At Gujarat’s port city, he remembers wrestling with a familiar feeling: of not fitting in. For one thing, everyone jabbered in Hindi, a language he wasn’t conversant with. The hostels were shabby, the toilets clogged up, so much so, that Suraj wondered why he had landed in such a gloomy setting.

Moreover, REC students contended with being “second-best.” Like uncontested class hierarchies, IIT entrants were deemed top-notch or first-rate, while others bore the tags of the “also-rans.” Suraj recalls how such tierization was imprinted in all their minds, with little attention paid to complex factors that led anyone to “crack” a particular exam.

To make things worse, in 1994, the plague broke out. All schools and colleges were shut down and Suraj headed back home, on a fatiguing 30-hour train ride. Net-net, the first semester was rather depressing, and Moraje, who had always been savvy in Maths and Physics, failed his Maths exam. He recalls a life-changing encounter with a Senior student at that point. The Senior said, “Either you wallow in self-pity or take your life in your own hands.”

Engineering His Turnaround

Fortunately for Suraj, the nudge was all he needed. From the second semester, he hit his books with a vengeance and found that he relished his Electrical Engineering coursework. Besides, he started exploring leadership arenas outside the classroom grind. IT Services had started taking flight in India, and Moraje and other REC peers resolved to carve their own pathways in a promising sector.

They initiated an Intercollege Festival – called SPARSH – to showcase their cultural and extra-academic talents. They also organized the institution’s first Tech Symposium. And forged a college brochure for placements. Suraj was quick to pick up a life lesson. That one’s mindset or attitude could alter one’s environs: “When you take charge, you can make things better.” In the midst of all this extracurricular hustling, Moraje stumbled on the raison d’etre for institutional learning: “I made amazing friends.”

At the end of his four years, Suraj had climbed from his first semester’s blues to the gold medalist position, graduating at the top of his Electrical Engineering class.

Overcoming Imposter Syndrome

With enviable unflappability, he attempted the CAT exam. He had, by then, an offer from Tata Unisys. But like other peers, he wished to expand his job prospects. When friends started receiving calls from IIMs, he assumed he hadn’t made it. Since his parents were in Bangalore then, they had received offer letters but hadn’t been able to transmit the news. As it happened, he received offers from all the IIMs, including Ahmedabad, Bangalore, Calcutta and Lucknow. His father urged him to pick the most prestigious one: IIM Ahmedabad.

The IIM campus, with its exposed brickwork, geometric contours, arches, and landscaped courtyards, was an architectural marvel. Designed by the American architect Louis Kahn, IIM-A’s spanking dorms and new-age classrooms fulfilled their creator’s charter: to imbue dreamer entrants with blue-sky thoughts. Moraje was among the galvanized, setting out to conquer the daunting terrain. Like many new entrants, he admits to being struck, at first, by imposter syndrome. Though he had been a topper at REC, Surat, here he faced off against the nation’s sharpest minds: drawn from IITs and other competitive settings. “Everyone was so talented, they spoke so well, they presented well.”

It took him the hindsight of twenty years to realize that many might have felt that way. He wishes, in retrospect, that a senior student had guided him and others, assuring them that such fears were inevitable and that things would work out anyway. Because, as it happened, even in this more competitive setting, Suraj landed Zero-day offers from one of the most sought-after employers: McKinsey & Company.

From Partner to Pioneer

He ended up spending twenty years at the storied consulting firm, becoming the first Indian to be appointed Partner in the European continent.

With disarming candor, Moraje admits that when he made Partner, he approached one of the Senior Partners to understand what it is that “Partners” do exactly. Absorbing tips from other Partners, the minutiae of their workplace routines, and fuzzier, big-picture moves, he sensed that he needed an arousing adventure. An intrapreneurial role within the firm that also had clear social spinoffs. After all, he was reaching a stage when he had started reflecting on impact in broader terms, beyond material compensation.

African Adventures, Asian Buildouts

McKinsey was setting up its Telecom practice in Johannesburg, South Africa. As someone who had grown up in the sunshiny continent, and was familiar with at least a few countries there, Suraj seized the opportunity. More significantly, he was keen on empowering ordinary folks with mobile connections.

The Johannesburg stint was a magical confluence of past and present. And it was thrilling to usher the future into countries throbbing with hope. South Africa, a young nation then, was a stirring cauldron of national and personal aspirations. Melding into that environment as a participant – rather than as a tourist or business visitor – was unforgettable. Suraj observes that you gain more from a place when you engage with ordinary processes: like applying for an electricity connection, shopping for groceries, or hunting for schools.

After five years, when the telecom practice was fairly even keel, Moraje sought a new scene. He set out to lead the Firm’s practice in the Philippines, a country where McKinsey was looking to boost its practice. After four years in the archipelagic nation, in which he built out a full-fledged consultancy, he chose to return to India.

From Jet-Setting to Building

For one thing, he had bumped against a personal health setback. More than that, after two decades in far-flung geographies, he missed the feeling of rootedness. He also had his wife and pre-teen sons to think about. Though the family had shared many exhilarating experiences, red-eye flights and intense workweeks had shrunk his presence at home.

At Bangalore, he moved to a live role, as the CEO of Quess Corp, one of the nation’s largest business service providers. “At Quess, we were creating high-quality blue-collar jobs, and a million people were able to eat dinner because of what we were doing, and that felt good.” At the end of an enriching two-year stint, that reinforced his penchant for building and running enterprises, he set out to create his own social foundation.

The Eka Fellowship: Fuelling Dreams

The Eka Fellowship intends to enable the social mobility of young aspirants. Picking their cohorts from low-income households, the Fellowship offers long-term career, cultural, and educational support to 8th Standard entrants.

Acutely attuned to how privilege begets privilege, the Fellowship plans to bridge the gap for motivated strivers. By handholding and mentoring fellows, till they enter the formal workforce, they aim to impart hard and soft skills that elite kids glean by default. So far, they have already organized day-long workshops and interactions with a host of professionals. For children, who haven’t explored the workscape beyond the much-touted “Engineering” or “Medicine”-led careers, encountering finance, advertising, theatre, and cricket professionals can be life-changing. As Suraj puts it: “It’s very gratifying to see the impact in such a short time.”

Exploring New Horizons

Besides running the Foundation, Moraje is also exploring other for-profit opportunities that might have social or environmental runoffs. He’s emphatic, however, about not being in a rush. He relishes his mid-life sojourn from the productivity treadmill, savoring time to read, reflect, cook, garden, and converse with his sons before they fly the nest. He does acknowledge that the break from 60 to 80-hour work weeks can feel foreign and even discomfiting at times. But it’s the kind of disorientation he’s been accustomed to overcoming at various points in his life. As an eternal optimist, he looks forward to unfamiliar vistas in new terrains.

Radiating the kind of beginner’s mind prescribed by Zen masters, Moraje says: “I’m 47 and I still don’t know what I want to be when I grow up.”

References