Struggles, Choices and Wisdom Across Generations

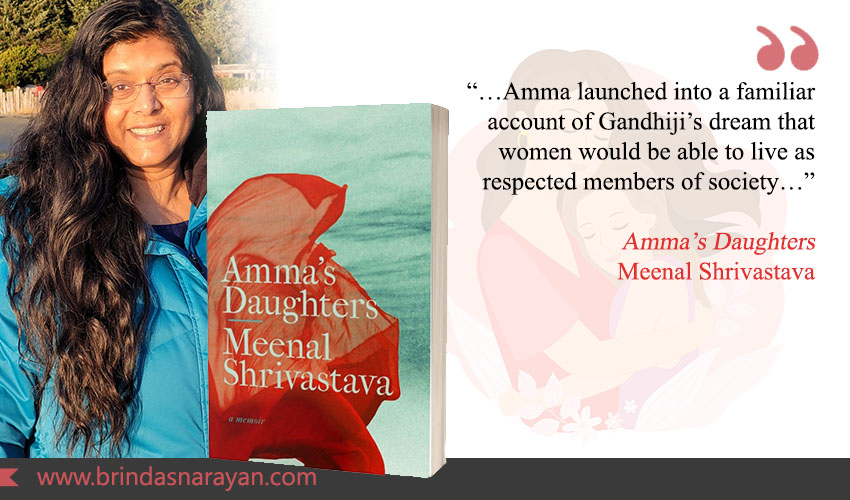

Amma’s Daughters: Evoking Nostalgia

Reading Amma’s Daughters by Meenal Shrivastava evokes the bittersweetness of listening to Kishore Kumar’s hit songs. It’s a book that yanks you – like the legendary singer’s tenor and baritone – into earlier times, into eras that might wrongly be characterized as “simpler”, given the kind of social and political upheavals that seeped into all spheres. Including, as Shrivastava, painstakingly depicts, into domestic realms, luring women away from their tedious tending of kitchen fires or other repetitive household chores.

Resurrecting Forgotten Lives

Before dipping into the book, a bit about the author: Vancouver-based Shrivastava is currently a professor of political economy and global studies at Athabasca University. In this work of creative nonfiction, she recasts the notion of a memoir. Rather than plumbing her own past, she resurrects the life of her grandmother, Prakashwati or “Amma”, and of her mother, Surekha.

Narrated in the voice of her mother, whose childhood and young adult years Meenal deftly inhabits, the first-person account reinforces the critical and forceful presence of Indian women through the nation’s freedom struggle. Reading this makes the starkly underwhelming presence of women in India’s current Parliament all the more heart wrenching and infuriating.

Indian Women: An Ignored Vanguard

As Meenal notes, “of the more than eighty thousand people arrested during the civil disobedience of 1930-31, some seventeen thousand, or better than one in five, were women.” Moreover, these women were not prodded into the public sphere by politically charged husbands, sons, fathers or uncles. Rather, quite often, the converse was true. Many women actively shamed their menfolk into adopting more courageous stances or participating ardently in the national movement.

It’s also a book that dispels another myth: that feminism is a Western import, and that traditional women in India required their “civilized” rulers’ sagacity to resist oppressive norms. As Shrivastava depicts, Amma could easily engage in sophisticated takedowns of gendered hierarchies with the archness and philosophical bent of better-known counterparts like Germaine Greer or Simone de Beauvoir.

Idealism Fuelled by Tragedy

Prakashwati, who was born Shanti, into a middle-class household, and whose life was permanently altered by the tragic drowning of her three sisters, was drawn into the freedom movement by chance. Spared from the river current that stole her sisters, a shivery nine-year-old Prakashwati was curled into the leafy branches of a tree. Spotting the runaway, two freedom fighters suggested she join them. Partly to imbue the numbed child with a mission, but also to give them cover from roving police.

Thus flung into the nation’s upheaval, her involvment was marked by a passion that only such searing trauma can fuel. Later, Amma was even willing to forgo marriage. It was, ironically enough, Gandhi who insisted that she marry and forge a family, a decision that her own daughters were to question in the future, given her unabated zeal for political and social activity.

An Offbeat Couple

Amma’s family then was unconventional, even by contemporary standards. Both Prakashwati and her husband, Babu – another idealistic zealot who was mysteriously absent for long periods – seemed perilously indifferent to household matters and to the raising of their two daughters. Babu, in particular, typified the kind of “missing father” whose ongoing vanishings could have emotionally scarred his kids.

Amma, as a single mother, was reluctant to shrink her public engagements. And was keen to impact the lives of other women, even if that meant, she had to lug her daughters across geographies and into and out of various supporters’ homes. But she also ensured that she kept the family going, earning for their needs and education, while contending with the on-off, and sometimes vituperative husband. Hers was the fierce spirit that bound them together, if in a now-and-then tenuous manner.

Fortunately, for Amma, she was supported by a vast network of women. Who empathized with her situation, and pitched in with household tasks or childcare. Even as they all had to contend with dual missions: of resisting the British while also battling misogyny and sexism.

Shrivastava does not shy from depicting her grandparents as flawed dreamers – folks whose social contributions may have been immense, but whose legacy inside the family might be more contentious.

Sisters, Fates and Ironies

This is also the story of Surekha, the narrator and Shrivastava’s mother. Who ended up doing a Doctorate in Hindustani Classical Music, and forged an independent life for herself. Who was drawn into the magnetic field of her parents’ feisty beliefs, but who channelized that energy into quieter, creative domains like art and music. Who, despite herself, met a man who swept her off her feet. An occurrence that surprised her since she had never dreamt of such an ending for herself.

Then there’s the parallel story of Didi, Surekha’s older sister. Who is graceful and polite, but also strongly resists her parents. Who deliberately chooses a life unlike theirs. Who, much to her father’s dismay and Amma’s apprehension, picks the “mainstream” by marrying into a traditional zamindar family, rather than inhabiting the fluidity that accompanies the radicals.

This then, as Meenal observes, is the irony: Surekha’s relatively offbeat choices were a form of submission, while Didi’s traditional life was a courteous and quiet rebellion. The work also reinforces how idealists too can be dogmatic, judgmental and often problematic inside their intimate circles, radiating a paradoxical intolerance in practice while championing tolerance in theory.

Promises Kept, Lives Remembered

Surekha always wanted to write this book. When she’s on her deathbed, Meenal promises that they would work on it together. After her death, Shrivastava sticks to her side of the bargain. This is a book that spans many Indias – pre-independence, and later. But some of the progressive views, voiced by Amma, could well be relevant to 21st Century India. When an observant Amma notices her dark-skinned Surekha ruing her reflection, she says: “What anyone else sees in you is extremely subjective, ever changing with time. What matters is what you discover and rediscover within yourself.”

References

Meenal Shrivastava, Amma’s Daughters: A Memoir, AU Press, Athabasca University, 2018