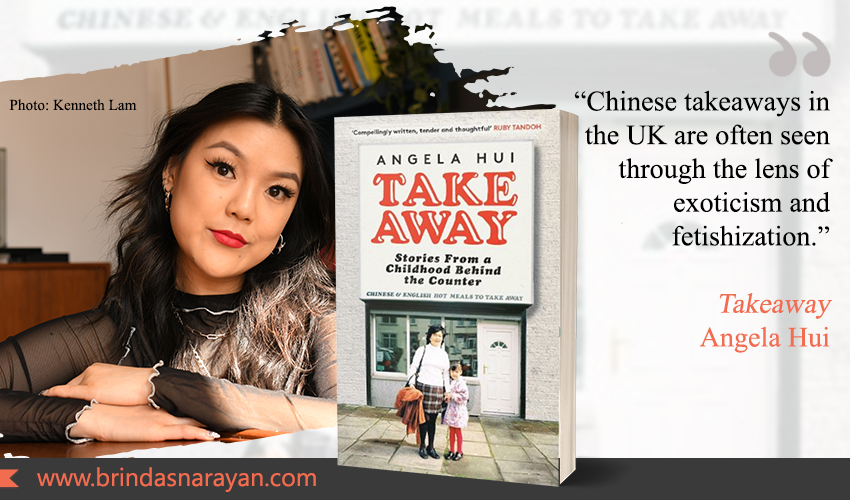

Growing up British Inside a Chinese Takeaway

One of the fallouts of the pandemic originating in Wuhan, China has been an unfortunate spike in anti-Asian crimes in the UK, US and in other parts of the world. As Angela Hui notes in Takeaway, besides widely publicized attacks like the March 2021 shootout in Atlanta – where eight people were shot dead, of which six were Asian women – “hardworking, family-run Chinese takeaways have been hit hard, targeted and vandalized.” This isn’t the first time the community has faced racist strikes. It’s a mere heightening of long-held historic prejudices that had been seething below the surface, breaking into contemporary news reports as sporadic incidents.

Angela herself was the child of a Chinese takeaway family: “All my life I’ve hated being East Asian, especially a Chinese takeaway kid, but how does a person learn to hate something that they were born into.” As a community, East Asians were considered “white adjacent” – similar enough to whites to wield a kind of privilege, but different enough to experience both explicit and subtle racism. Hui’s parents had always, like many first-generation immigrants to the UK, encouraged her to assimilate and fit into the mainstream.

Chinese Takeaways in the UK

Later, as an adult, she has been unwilling to suppress her voice. To stay polite and to belong uncomplainingly to boxes her family was thrust into. The book is perhaps one of the ways in which she is both reflecting on her past and speaking out.

Chinese takeaways, she notes, had always been diminished and disparaged. Workers were framed as “unhygienic” and “unskilled” despite these outlets trying relentlessly to adapt to local palates and introduce innovations. “They’re willing to bend the food and bend the culture for what their clients need, serving anybody who would pay them.”

Such takeaways sprung up in the UK in the 1950s, post the second world war. Since then, they have mushroomed across the nation, growing to about 9,500 in 2002. Their spread reached a point when there was typically one such enterprise in every village. Since these takeaways were reluctant to compete with each other, they rarely co-located in a single area. This also placed a larger cultural burden on Chinese families, who were required to embed themselves in predominantly white neighborhoods, while living at a distance from others of their ethnic group.

Lucky Star: The Hui family’s Takeaway

In 1985, Hui’s parents left Hong Kong for what they considered a “better” life. They hadn’t been educated themselves. Her mother had fled her famine-struck village, after the Cultural Revolution. Her father had been a high school dropout, hawking noodles in a cart from the age of 13. When they later emigrated to the UK, they moved from place to place, searching for jobs and accommodation. They finally settled in Wales and opened their own takeaway, calling it “Lucky Star.” While the name symbolized the Chinese belief in Luck and Good Fortune, it had been carefully crafted not to collide with other takeaways in proximal regions.

The family inhabited a town called Beddau, in the South Wales Valley. Behind their home, shuttered coal mines signified the joblessness and despair that had set in during Thatcher’s time. With a small population of only 4000 people, Beddau was the kind of place where everyone knew everyone. This, as Angela notes, “was both a blessing and a curse.” Most people around them were white; the chitter-chatter and buzz of a typical Chinatown was absent from their lives. But the stunning landscape around them was a consolation. Sheep grazed on rolling greens, ribboned with bubbling rivers.

Settling into a Welsh Community

The Welsh people, contending with tough lives, exuded a kind of rough hopefulness. And a sparky mischief. Relations were not always characterized by prejudice or racism. Many Welsh neighbors displayed a growing affection and concern for the Chinese family settled in their midst. For example, the local hairdresser would greet Hui with: “Dawn! Alright, love? How’s yer mam doing? Tell her I said hiya.” The book, as Angela observes, is not just the story of immigrants, but is also a quintessential British narrative. Of how the country simultaneously tolerates, embraces and rebukes immigrants.

Raised Inside a Takeaway

Hui also had to contend with being raised differently. Her Mom was “typically” Asian in her parenting: “overprotective” and “overbearing.” Moreover, the kids – Angela and her brothers – were expected to help with takeaway tasks from an early age. For instance, when Hui returned from school with a few school friends, her Mom would foist packs of spring roll wrappers on Angela. The kids were asked to unpeel each layer, while Mom grabbed a five-minute rest. Hui didn’t mind helping, but she resented the long hours, which cut into her socializing. “I found it hard to make new friends and became a bit of a hermit who kept to myself.”

Before the counter opened, she preferred that her friends leave. She preferred that they interact as minimally as possible with her embarrassing parents. Who didn’t speak English, who didn’t get Welsh ways. She would have loved to leave with her friends, but she didn’t dare invoke her parents’ ire. She was torn by contradictory feelings: a child’s natural urge to hang out with peers, and a daughter’s guilt about deserting parents, who were on their feet day and night to keep the home fires burning.

The counter divided in other ways. It separated the relatively free customers from shackled workers. One was allowed to order, the other compelled to take orders. “We’re both humans, the only difference is one is standing on one side of the giant plank of wood running across the room and the other behind it.” But it also unified. For instance, their 60-year-old Welsh assistant Cecilia became like a faux-grandma to Angela. She helped fend off male advances, which 12-year-old Hui had to otherwise thwart on her own.

Reflections on Her Childhood

Later, as an adult, she’s grateful for gleaning valuable skills from those early days in the kitchen. And for being kept off the streets and the kind of trouble teens and young adults might get into. Some of those tasks – like whisking eggs into a homogenous yellow – might even have imbued her with a meditative calm. Other jobs, however, were decidedly ghastly. Like deshelling prawns. She had to contend with stung fingers and fish odors that clung to her clothes regardless of how many times over they were laundered.

The takeaway was also a place that gathered people together. And like any town center, was a witness to many scenes – customer brawls, sports events being collectively celebrated or sighed over, birthdays commemorated. A space that hosted mahjong tables as well as “an unofficial Six Nations rugby viewing where chips and fried rice” were scattered about.

A takeaway for readers from Hui’s book? It’s not just immigrants that have to adapt to their host environments; countries have to change too, if they wish to leverage the talents of striving entrants.

References

Angela Hui, Takeaway: Stories From a Childhood Behind the Counter, Trapeze, 2022