Celebrating the Wonders of Russian Literature

Russian Writers Probe Existential Depths

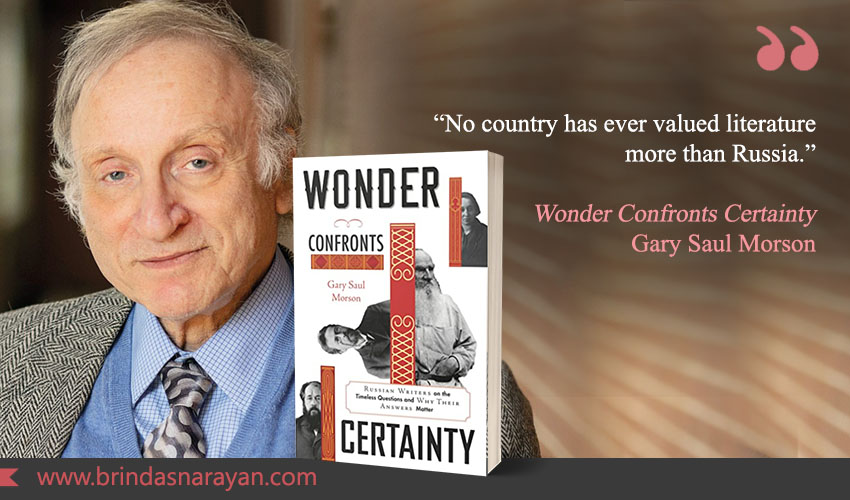

In Wonder Confronts Certainty, Gary Saul Morson, one of the most eminent Slavic scholars in the US, suggests that Russian writers were a distinct breed. We’re talking about the heavy weights of previous centuries. Legends like Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev and Chekhov. Unlike their American and European counterparts, Morson observes that the Russians delved into deeper questions. Metaphysical ones about faith, God, belief or its absence. As well as related ones about the meaning of existence. As the author puts it, “The English wrote about manners, the Russians about the soul.”

Viginia Woolf agreed. Reading the Russians with the raking sights of a fellow-writer, she notes about their depictions, “we are souls, tortured, unhappy souls, whose only business is to talk, to reveal, to confess.” In their works, Woolf continues, we glimpse the bared soul, “its passions, its tumult, its astonishing medley of beauty and vileness. Out it tumbles at us, hot, scalding, mixed, marvelous, terrible, oppressive – the human soul.”

In other words, one did not read the Russians for enjoyment. These books were meant to provoke audiences, to raise discomfiting questions, to “[shock] them into reexamining their lives.” Given the historical forces that shaped these writers, it’s almost inconceivable that facile goals like “pleasure” or “satisfaction” were even on their minds. After all, many lived through terrors that were of a scale unfathomable to others: famines, genocides, labor camps. These terrors swept through the population, overwhelming all sections till they swallowed “literally everyone except the ruler.”

Suffering Reveals True Character

As witnesses to such tumult, the novelists were quick to discern that true character emerges during duress. For instance, inside the Gulag (labor camps), many of the educated were more willing to renege on principles than the religious or faithful illiterates. Faith imbued the latter with a capacity to sacrifice themselves that rational, scientific thinking did not. As Morson asks, “Was Tolstoy right that sometimes sophistication leads one further from truth?”

Russian Roots of Many Literary Works

Russians had created many originals, their works inspiring well-known American or European spinoffs. For instance, the Russian novel, We, by Eugene Zamyatin was the progenitor of other dystopian works like Orwell’s 1984, Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 or Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. In We, obedient citizens who are all known by numbers, live inside a glass building, and are constantly watched over by One State – under a panopticon-like surveillance that has eerie echoes in contemporary lives.

Unveiling Complexity in Realist Fiction

But fantasy seemed to be less of a Russian thing than realist drama, drawn from the minutiae of human experience. They believed in writing fiction that “focused on the complexities of human psychology and the social conditions peculiar to a specific time and place.” Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, among the realists, felt that many other Western works were not “realistic enough.” They also played with form, tucking pieces of non-fiction into their works – essays, sketches & parables.

Tolstoy felt his own capacity to capture reality stemmed from his deep observational powers. Morson notes that writers like George Eliot and Tolstoy knew people “better than the greatest psychologists.” In Anna Karenina, the painter Mikhailov rejects the notion that he has any special talent. He says his artistry emerges “from his constant practice in noticing what others miss.”

Writers Who Radiated Wonder

Wonder Confronts Certainty swivels around a central premise. That there are certain writers who evoke wonder, because they are filled with questions themselves. They don’t pretend to know answers, or the truth. They realize that writing and reading propel self-discovery, rather than being the cavalier expressions of self-righteous truth. Writers who belong to the wonder category include Leo Tolstoy, whose characters like Levin in Anna Karenina or Andrei in War and Peace pose questions that might stir any deep thinker.

Or the Nobel-prize winning Svetlana Alexievich who forged a form of “non-fictional literature”, imbuing journalistic snatches with literary panache. She was, more than anything else, attuned to overlooked voices. For instance, she captured the often-missed women’s perspective on war. Or the war-time reminiscences of children. Or the suppressed stories of Chernobyl victims. Alexievich even calls “suffering” a form of capital, which gives birth to new material.

Another titan of wonder was Tolstoy’s contemporary, Dostoevsky. Who had rightly foreshadowed in The Possessed, the totalitarianism that would engulf Russia. And who, after the instigation of judicial reform in 1864, was critical of the new system. Though the overhaul was intended to ensure justice for ordinary people, Dostoevsky recognized that a clever, glib-talking lawyer could tilt the scales in his or her client’s favor. Which made “justice” subject to the calibre of one’s lawyer rather than one’s inherent guilt or innocence. Such a lawyer features in The Brothers Karamazov as a character.

Villains Who Embodied Certainty

Those who exude certainty include folks like Lenin. Who refused to contend with alternate possibilities or the greys baked into any situation. Or Stalin, who owned, ironically enough, a vast library of more than 20,000 books. And who was a reader too, bringing into question the supposed loftiness that great literature should inculcate.

Role of Literature in Russia

Morson emphasizes the centrality of writers and literature to Russian life. Most people would believe that literature reflects or mirrors life. Russians might think that life exists in order to feed literature. “Like Jews, Russians are people of the book – or rather, books.”

Often, people read the same book together. During glasnost, popular books included Doctor Zhivago and Life and Fate. Everywhere you travelled in Russia, in buses or metros, people would be holding one or the other of these two books. In The Train by Shalamov, the narrator visits a used bookstore, not to buy books, but just to touch and feel them, and hold them in his hands. “To hold books, to stand next to the counter of a bookstore was…like a glass of the water of life.”

Russian Zeal for Action

But Russians are unwilling to merely muck about with theory. Unlike Europeans who held radical opinions, but lived conservative lives, Russians acted on their ideas. Morson writes, “To be Russian was to be immoderate.” For them, anything that progressed at a slow pace was unacceptable: “Evil must somehow be eliminated at a stroke.”

In the light of Russia’s ongoing war with Ukraine, one would wish for ordinary Russians to practice a bookish protest. By retreating into libraries and burrowing themselves in tomes, rather than wading into an unjustifiable and futile battle.

References

Gary Saul Morson, Wonder Confronts Certainty: Russian Writers on the Timeless Questions and Why Their Answers Matter, Harvard University Press, 2023