Unpacking Contradictions in Indian Masculinities

A Portrait of Raj: A Young, Middle-class Indian Man

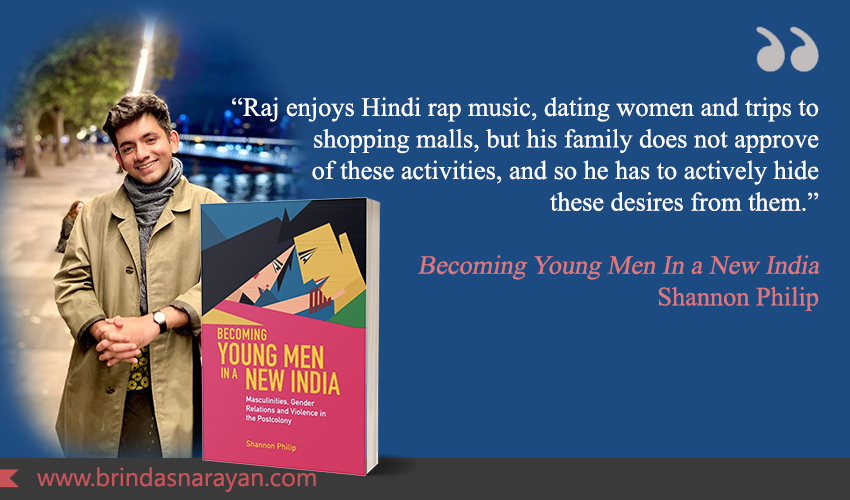

Raj, 24-years-old and a member of the Indian middle-class, hates auto drivers and woman drivers with equal fervor. He discourages his own sister from learning to drive, and only dates women who “like to be driven around.” While ranting on in this manner to Shannon Philip, he’s interrupted by a call from his father. He immediately shushes Philip into silence while he lies to his Papa about his current doings. He says he’s headed to college, for extra classes. Later, he turns to Shannon and says: “Bhenchod (sister-fucker)…My parents are constantly on my ass.”

The Author Embarks on An Ethnographic Study

Shannon Philip, who is currently a Lecturer in Sociology at the University of East Anglia, conducted an ethnographic study among young men who inhabit “new” India. This is an India that pulses with intensely material aspirations. With small-town and big-city dreams. A terrain that invites change but also stalls it, especially when transformations can discomfit established social orders or cultural hierarchies.

Paradoxes in Raj’s Life

As a sociologist, Philip observes contradictions that are stitched into Raj’s life.

- He seeks a comfortable life in an unequal landscape. Which, of course, could be said for many of us belonging to the middle and upper-middle classes in India.

- He prefers that his own sister does not drive; at the same time, he has no qualms about flinging terms like “bhenchod” – which belittle women.

- He likes Hindi rap, dating and shopping malls.

- But he also has to camouflage these activities from his family.

Raj, of course, is only emblematic of other young, middle-class men. Shannon tries to unravel the effects of their angsty psyches on the social fabric of contemporary India.

When The “Good Life” Violates Parental Norms

In general, for young men like Raj, a “good life” comprises:

- Visits to shopping malls

- Sex before marriage

- Dance clubs and bars

To them, this embodies modernity, with a concomitant sense of freedom. This kind of consumptive, leisurely life bumps against strictures imposed by traditional families. As Raj himself comments to Philip: “India has changed, I want to have a good life and live freely, be modern, not remain stuck in the past.” Such desires keep rubbing up against parental injunctions to not drink, smoke or mingle with women till they find him a suitable bride.

Many young men, as a result, carry these paradoxes inside themselves. This often plays out in unhealthy ways – as violence inflicted on women, or as ongoing deceptions with their families and future partners.

The Male Seizure of Public and Private Spaces

These men also start owning certain spaces – like gyms, clubs, parking lots, malls, cafes and metros. In the process, they displace women and those from lower income groups. Because of frequent cat calls or other unwelcome advances from such men, women start finding these spaces unsafe. As Philip puts it, these young men “foster a sense of gendered, sexual and classed entitlement over these spaces and the bodies within them. They decide who belongs and who does not, who is safe and who remains in constant fear.”

Indian Modernity Forges A Particular Male Culture

India’s embrace of modernity also spawns a particular culture – one that prioritizes a competitive, corporatized, commoditized self. This process of “modernizing” the nation does not simply involve mimicking the West. Rather, as the scholar Makekar observes, it’s about “Indianizing” modernity.

This doesn’t mean we necessarily have a salubrious or more healthy notion of modernity. Rather, we are creating violent internal fissures, especially in “youth”, who are seen as agents of economic and social progress. Such consumption is also gendered and targeted largely at urban dwellers. As Manali Desai points out: “For the new, urban, middle class India, hedonism, voyeurism and sexual prowess are eternally emblazoned on the cities’ and highways’ larger-than-life billboards, in films and, not least, in a vast amount of pornography. The aspirational gym-toned male body, with distinctly Western consumer tastes – whiskey, cigarettes, fast cars – looms large on city billboards, enjoining men to participate in the image, if only vicariously.”

“Urban Smart Strivers” Pursue Leisure

Drawing from the NCAER 2004 report on the “Great Indian Middle Classes” which has a category labeled “strivers”, Philip uses the term “urban smart strivers” to describe the young men that he’s studying.

In this lot, while work and education continue to play a significant role, there is an increasing emphasis on leisure. This also entails a new ‘urban leisure architecture’ which largely impacts masculine identities. Many men accumulate degrees and skill certificates, but they lack the social and cultural capital to land jobs. Or their educational settings have been inadequate in transmitting know-how, but have succeeded in resetting aspirations. As a result, Shannon notes that many in this group “face extended youth” and “low employment opportunities”, and they imbibe notions of “uselessness” and “worthlessness.”

Passing Time Amidst Accelerating Change

Rather than accept a job that might impact their social standing, they get trapped in a politics of waiting. The “timepass” crowd, with their in-bred frustration, is leveraged by political parties or criminal organizations to inflict violence on women or other marginalized groups. As a result, “new” India witnesses growing levels of male violence against women.

Strivers also encompasses the notion that these men are always in the process of “becoming” but never quite getting there…the “strivers are chasing an image and way of being that has not quite materialized, and perhaps never shall..”

Male Roaming As A Favored Past-time

Besides waiting, another favored activity in this group is “roaming.” “Ghumne” on bikes or buses or metros imbues young men with a sense of freedom. For one thing, in this manner, they can traverse cities and spaces at will. And also distance themselves from badgering families.

Roaming also fosters participation in homosocial spaces, where these men indulge in “sex, drinking, smoking, shopping, horseplay, jokes and violence.” When Shannon accompanies a young man called Kartik, the latter points to a slum as the kachra (garbage) that has to be removed.

While these men cherish their ability to freely roam, they do not think that women should be granted similar liberties. They see themselves as “protectors”. As Raj told Shannon: “I am a modern type of man, I care about women, they are in real danger in Delhi and so I am very protective about my girlfriend and my sisters, I never let them go out alone.”

Cat Calling Women

Men like Raj also don’t think it’s wrong to “touch” women or hurl flying kisses at them. All this while vilifying the poor as violent rapists. They frame their own activities as “innocent fun,” even as they make the spaces in which they hang out uncomfortable for women.

Emphasis On Male Grooming

They are also into grooming themselves, much more than men of earlier cohorts: hairless, fair-skinned chests are often an aspirational ideal. As a result, men’s grooming products are growing at twice the rate of women’s products.

Women, too, have to groom and consume to fit into these spaces.

Historic Constructs of Masculinity

While “military” careers were valorized in pre-colonial times, under the British Raj, Indian masculinity was framed as being inadequate or not masculine enough. Organizations like the Arya Samaj tried to address this by altering Indian male bodies with discipline and new regimens. This often entailed curtailing sexual urges and food, while engaging in activities like wrestling.

During the Gandhian movement, there was a greater emphasis on inner morality.

Post-independence, there have been cinematic shifts in the portrayal of masculinity. Moving away from the angry young man who often represented the interests of the powerless, the post-liberalization hero focuses more on his own grooming and fashion. “…this consuming masculine figure is spatially depicted most often inside shopping malls or driving fancy cars and travelling abroad.”

The Social Production of Violence

While Philip recognizes that India has “multiple cultures of masculinity,” this book takes a deeper look at the manner in which violence is built into gendered constructs: “making violence not something ‘extraordinary’ but socially produced.”

It’s a critical read to grasp the manner in which economic changes collide with social forces, resulting in both progressive and reactionary spinoffs.

References

Shannon Philip, Becoming Young Men In a New India: Masculinities, Gender Relations and Violence in the Postcolony, Cambridge University Press, 2022