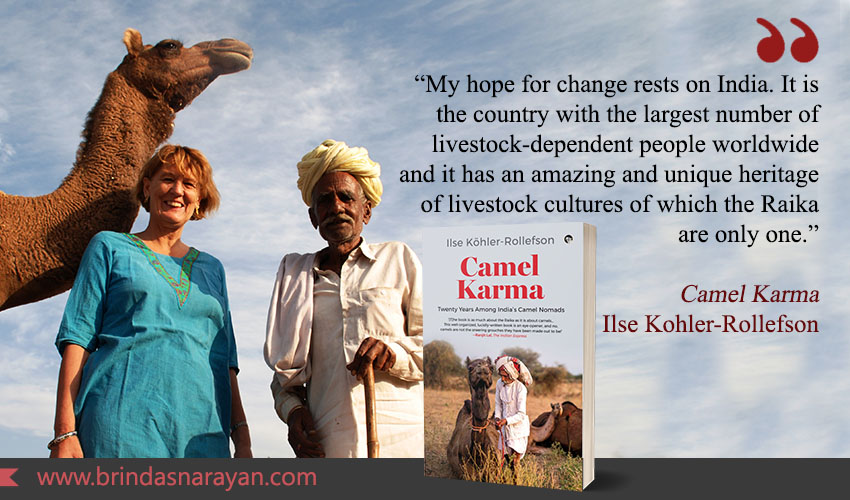

Camel Karma: Transforming Desert Lives

Rajasthan is often framed in touristy stereotypes: of forts, palaces, erstwhile maharajas, sparkling sands of the Thar Desert, and camels no doubt, offering a discomfiting, double-humped ride through arid lands. Only a few would be acquainted with the complex ecology surrounding traditional camel breeders, their camel herds, and the threats faced by a vital pastoralist lifestyle. Camel Karma is an eye opener: not just in the way it paints Raika (nomadic camel breeders) lives, but also in depicting Ilse Kohler-Rollefson’s gritty journey to champion pastoralist rights on a global stage.

Falling in Love with Camels

Ilse, who grew up with horses and other animals in Germany, became enthralled by camels while on an archeological dig in Jordan. A vet by training, she was tired of her routine jobs in the rural German area, where she worked. At the dig, she needed to analyze animal bones to figure out their diet and other related “faunal” information.

In the distance, she spotted a camel herd and was struck by how orderly and obedient the animals were. While drinking water, they took turns in careful batches, submitting to the commands of a single Bedouin herder. Baby camels frolicked and seemed to play ‘tag’, occasionally returning to even-tempered mothers. The human-animal interactions were strikingly different from those at industrial farming sites she had observed in Germany. Here both humans and animals seemed more peaceful, co-existing in a mutual give-and-take.

Tellingly, the Arabic word for camel is “jamal” – which means beautiful. Obsessed with these double-humped creatures, Kohler-Rollefson wrote her doctoral thesis on their domestication.

Camel Wisdom: Footprints and Pagris

Since India has the third-largest camel population in the world, after Somalia and Sudan, she landed in Bikaner, to conduct research on camel husbandry under the aegis of the National Research Center on Camel (NRCC).

But she could find little literature on camel breeders or camel management from India. Most papers were about camels – their habits or their biochemical makeup – but there was little about their human caretakers.

The Director of the NRCC sent her to Gadhwala, a Raika village, a few kms from Bikaner. There she met with Kanaram, a Raika breeder. His animals were freely wandering about 20 kms away, but he was confident that they would return to drink water at a particular well. Besides, they had “pagris” – people who could read animal footprints. He said they could figure out which footprint belonged to which camel, and could even read a footprint to discern if a camel was pregnant.

Milk Taboos and Sand Diagnoses

More intriguingly, Kohler-Rollefson learned that the Raika did not sell camel milk or eat camel meat. As she gradually encountered more Raika, she observed that they occasionally drank camel milk, but did not eat the meat. They also used other camel by-products, but clearly the economic returns from a camel did not seem optimal. Mostly, they bred female camels to give birth to male camels that could be sold to other castes for work.

In the village of Sadri, where she met more breeders, she was struck by how a half-naked child was allowed to meander between camels. At vet school, she had been taught to fear large animals. “But these camels resembled family members and were treated almost as intimately; nobody was afraid of them.”

Chai Talks: Healing Hooves Together

She watched one of them test for a disease called “tibursa” – a parasitic condition – by smelling a sand ball containing the animal’s urine.

One of the Raika camel breeders, Adoji, told her that the animals had suffered many miscarriages and hence the camel population had really dwindled. Ilse was flustered, because he expected her to solve his tribe’s problems – fix the camels’ medical issues and improve their grazing situation.

She also realized that she wouldn’t gain much as an objective academic. She needed to be involved in their lives in a tangible way. And also spend long hours chatting and drinking tea, before they became comfortable enough to impart information. “Taking tea, especially, was kind of an acid test…” But how much could she contribute as a foreign researcher?

As it turns out, plenty. Because over the years, Ilse’s life became braided with the Raika and their camels – establishing a long-term, affectionate interchange that permanently altered all.

Milk, Money and Medicines

For one thing, she gently challenged the taboo around the sale of milk. The Raika believed that selling milk was akin to selling one’s children: “dudh bechna, beta bechna”. But research indicated that camel milk offered huge nutritional benefits, and one could see the health effects on the Raika themselves. Who drank milk raw or with tea, and remained lean and physically hardy.

Ilse also paid attention to their grazing issue. Swathes of forest had been enclosed by the Govt and were no longer available. This was supposedly to preserve trees, but the Raika felt that loggers were cutting those trees anyway. The forest was turned into a wildlife sanctuary – the Kumbhalgarh Reserve and the area for camel feeding had shrunk drastically.

Along with a local vet, she set up a society – which included the Raika as members – to represent grazing rights. She also raised funds in Germany to inject camels with a “teeka” or injection that would prevent the parasitic disease, while being careful to collect data about the efficacy of the medicine.

Frequently traveling to the Pushkar camel fair, she even bought a camel to accord herself with an owner’s stake in the community. And entrusted someone to care for it. “Mira” – the camel baptized by Ilse – had a red ribbon tied to her tail, to signify her sale.

Abiding with Shoes and Spices

Teaming up with an Indian professor, she organized a conference about Raika, with Raika participants as an active voice. It was such a heated debate, that at one point the scientists and Raika pummelled each other with shoes. At the end, though, the Raika put forth demands required by their community. Ilse then set up the League for Pastoral Peoples in Germany.

Despite contending with ongoing digestive issues – Ilse couldn’t stomach the spicy Rajasthani curries or their ghee-laden parathas – compelling her to subsist for months on end on just biscuits and bananas, despite having to parent her own school-going twins and accommodate her anthropologist husband’s career needs, she never gave up on her mission.

Camel Chronicles: Trailblazing Tails

Which grew wider and deeper, touching Raika lives in multiple ways. She founded many organizations, including the Camel Husbandry Improvement Project (CHIP), promoted the study and documentation of ethnoveterinarian practices (the melding of traditional and modern approaches to treating camel diseases), highlighted the Raika’s grazing needs at the World Parks Conference (2003), and embarked on an 800 km yatra to raise awareness of dwindling camel numbers. She even escorted a group of Raika, including a colorful Bhopa to Germany and then to Interlaken, Switzerland for an FAO conference.

Even as India heads to a trillion-dollar future, Camel Karma is an urgent appeal to heed the dilemmas of desert nomads and traditional pastoralists; and to also imbibe aspects of their relatively slower, ecologically-bound lifestyles.

References

Ilse Kohler-Rollefson, Camel Karma: Twenty Years Among India’s Camel Nomads, Speaking Tiger, 2023