Choosing to Live in Magic: Somak Ghoshal Forges a Creative Life Path

Somak Ghoshal: Discovering the Riches of English Literature As a Young Adult

The Mint Lounge has always been a favourite weekend read. Especially the book reviews that dissect the profusion of works spawned by Indian authors. While the Lounge, overall, is peopled by a particularly gifted set of writers, I’m expressly captivated by the pieces penned by Somak Ghoshal. He not only evokes a book’s texture and theme within a tight space, but crafts his own sentences so deftly and precisely, that I often wonder if the author’s words will match those of the reviewer. Meeting him at the Matteo Café on Church Street feels like the closest I will get to the Bloomsbury Set, the writers, philosophers and artists who inhabited the now-famed district of London in the first half of the 20th Century.

Given Somak’s proficiency in English literature, it’s astonishing to learn that till the age of 16, his first language was Bengali. Till he reached the 10th Grade, he had studied only Bengali Literature and read Bengali fiction, including many works of European literature that had been translated into Bengali. And then, like many readers who are tugged into the riches of a second language by a work that stirs them personally, he encountered The Shadow Lines by Amitav Ghosh.

In the book, Ghosh paints, in his distinctively visual style, the sounds, colors, and the shocking linkages between riots that ripple through Calcutta and Dhaka. Ghoshal remembers a seismic shift, when he recognized his own local universe being brought to life, in the “foreign” language. Moreover, Amitav Ghosh seemed to exhibit a sensibility that was stylishly cosmopolitan while staying rooted in his origins – a feat perhaps, that Bengali creators like Rabindranath Tagore and Satyajit Ray had exhibited in the past. From there on, Somak started reading as extensively in English as in Bengali. Another breath-stopping moment occurred when Arundhati Roy released her startlingly original The God of Small Things. Since then his reading has stayed deeply bilingual.

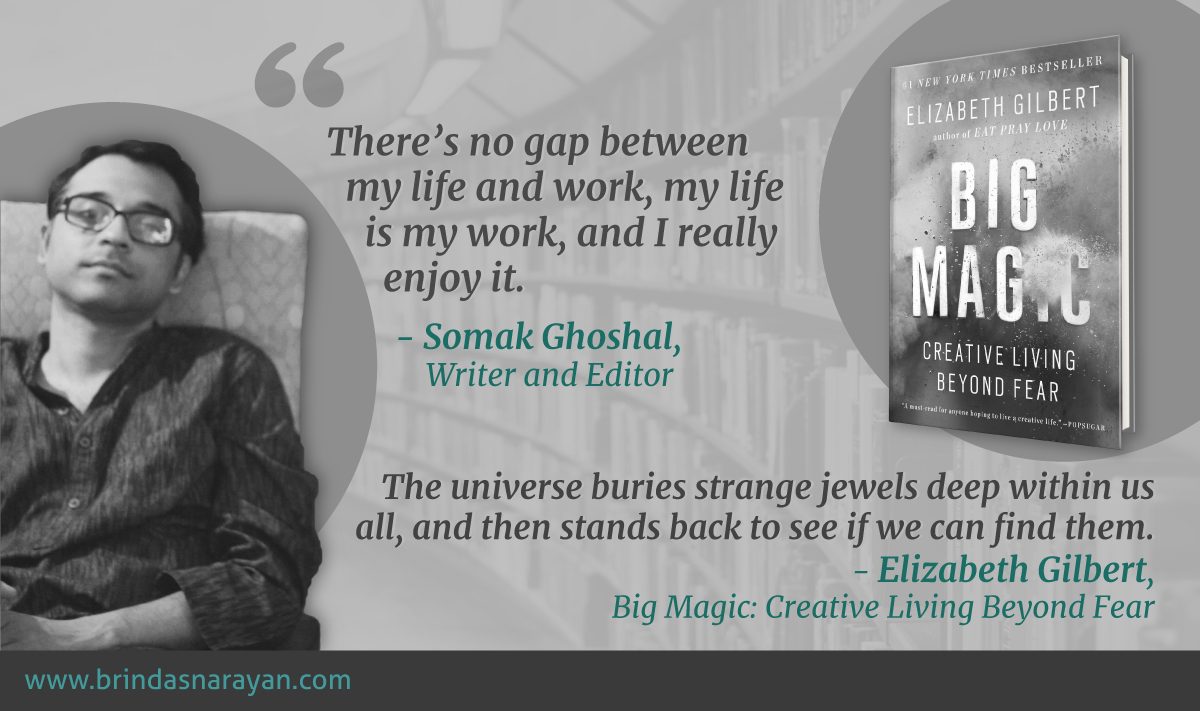

Big Magic: Overpower Your Fear When Embarking on a Creative Journey

For many Indians, like Ghoshal, a familiar emotion that accompanies late-stage forays into English might be fear or diffidence. Growing up in America, Elizabeth Gilbert did not have to deal with linguistic complexities. But she understands fear, because as a child, she was prone to exceptional levels of anxiety. It was not just the normal things that scared her – like darkness and ghosts. But even seemingly benign things like “snow, perfectly nice babysitters, cars.” Her mother, however, did not cave into her fears, and deliberately exposed her to the very things she was most afraid of. She fought and resisted till she grew into an adolescent, and suddenly she realized that she was needlessly limiting herself by “defending” her weakness. She found fear boring, so she decided to let it go.

She understands, that on any creative journey, fear is an inevitable and to some extent, even a necessary companion. She even chides “Fear” as a co-passenger on the ride to the Destination Unknown: “You’re allowed to have a seat and you’re allowed to have a voice, but you’re not allowed to have a vote. You’re not allowed to touch the road maps…above all, my dear and familiar friend, you are absolutely forbidden to drive.”

Somak Ghoshal: Eschews Conventional Paths to Weave His Life Around His Interest

For Indians of his generation and coming from a middle-income family, Somak chose to embark on an audacious career path by pondering his own interests. Though he had chosen to do Science and Maths in the 11th and 12th Grades, he realized he was more enticed by English Literature. He opted to pursue a B.A. in English at St. Xavier’s and then a two-year Master’s in Jadavpur University. He recalls meeting excellent mentors at Jadavpur, and still cherishes those years as being a memorably formative period. In 2004, he embarked on a second Master’s degree in English, from Oxford University. He had also won a scholarship to fund his U.K. stint.

The structure of the Oxford program involved tutorials – wherein, Somak met his tutor once a week, authored an essay on an assigned topic and discussed the essay and the reading list with his tutor. With such intensive writing practice, under the persistent scrutiny of tutors, he learned to “write by [his] ear, not by [his] eyes.” Moreover, he started attending to the elegance and allure of each sentence. Such writing was bolstered by his equally extensive reading. For instance, if the topic related to Shakespeare, Ghoshal was expected to read all of Shakespeare. Tutors not only assessed their writing and opinions, but also the degree to which they had imbibed their texts.

With plans to embark on a doctorate later, he returned to Kolkata and joined The Telegraph as an Assistant Editor. Since he wrote extensively on the arts and on books, he found, soon enough, that he enjoyed sparking conversations on culture among lay readers, besides the exhilaration of spotting his own byline in print.

Big Magic: The Inexplicable, Magical Source of Ideas

Like Somak, Gilbert discovered her own interest in writing at an early age. At the age of sixteen, she describes going down on her knees and vowing to become a “writer” in a manner in which most people will summon an inexplicable Higher Force.

But even after many books, including the wildly successful Eat, Pray, Love, Elizabeth believes that something magical is at work, when it comes to creativity. With a charming earnestness, she sets forth a world composed of plants, animals, human beings and ideas. And a proposition that each idea is waiting for a willing human host to alight upon. Once the host decides to engage with that idea, the “idea will organize coincidences and portents to tumble across your path, to keep your interest keen.” At some point, the idea will propose to you like a swooning lover: “Do you want to work with me?”

If at that point, you decide to engage with the idea, you embark on a contract to almost destroy yourself and everything else around you to bring the idea to fruition. But there are times however, when you cannot immediately or even continuously persist with the idea. When you return to it later, in some cases, you will find its power has vanished. It no longer attracts you and you can no longer embark on that journey. You need to hunt for a new one.

The poet Ruth Stone confirms Gilbert’s magical take on ideas. Stone describes times when she is working in the field in Rural Virginia, and she can feel a poem “galloping” towards her, and she needs to rush back home, grab pen and paper and write it down at once, before it departs. There are times however, when it’s too late, when the poem vanishes, and she has to wait for another one to arrive.

Elizabeth also interviews the singer Tom Waits, who has learned to abide with the whims and shifting fancies of Inspiration. Some songs come to him easily, “like dreams taken through a straw.” But others need to be plucked out of weird places like sticky gum. With some, he engages in a sort of confrontational dialogue. In such instances, he asks the rest of his crew – his band members and assistants – to quit the studio. Then, alone with the recalcitrant song, he commands it to come to him or suffer being left out of the album. Some songs succumb to his dire threats. But others obstinately or mischievously elude his grasp. He has no choice but to let them go.

Big Magic: Use Curiosity to Discover Your Field of Interest

What about people who are not merely struggling to trap ideas, but are unsure about which domain or field to pursue? For such people, Gilbert encourages them to stay Curious rather than Passionate. After all, as she puts it, everyone can be curious and exploratory. She says Curiosity only asks you one easy question: Is there anything you are even mildly interested in? In other words, the interest need not be wholly absorbing or compulsive at this stage. It should merely lead you to take the next step and the next. Till you are possibly entering a different, unexpected terrain, which could very well turn out to be your passion.

Somak Ghoshal: From Media to Publishing, and then Back to a Morphing Media

Even when you have stumbled on a field, you are often compelled to take detours and explore related or different terrains. In 2011, Ghoshal changed domains and moved to publishing. He was appointed the literary fiction Editor at Penguin India at Delhi. While he enjoyed his experience at Penguin, he felt encumbered by commercial pressures and decided to move back to journalism.

For a couple of a years, he returned to newspapers, reviewing books for the Mint. Then Harper Collins approached him to manage their nonfiction list as a Managing Editor. He recalls launching many debut authors during that period, including White Magic, by Arjun Nath, a narrative about drug rehabilitation, and The Story of a Brief Marriage, by Anuk Arudpragasam, a novel that won the DSC Prize in 2017. Later, since he wanted to be based in Bangalore, he moved to HuffPost, covering general news and features. A couple of years later, he was back at the Mint Lounge again, working on a wider remit this time beyond the Books section.

Given that online activities can also erode attention, I ask him how he manages to keep up with his intense reading and writing. Somak admits that he has noticed personal declines in attention in the last two years. But he’s also found ways to tackle it. “Increasingly, I divide my time into chunks – for instance, in the next 30 minutes, I will not call or email.” Sometimes, he sets a pages-to-be-read target: “I will not do anything else, till I read 100 pages.”

Besides his professional pursuits, Ghoshal has recently mined his own emotional stores to author his first book. When Somak was only six-years-old, his mother passed away. With the tenderness and nuance that only someone who has borne such a loss can evoke, Piku’s Little World (Pratham Books, 2020), depicts how a child explores the landscape of grief and bewilderment. And magically emerges from the terrain with newfound powers. Illustrated by Proiti Roy as brilliantly as it is written, the book is a lyrical and sensitive introduction to death and loss for young readers. He is currently working on another book on human rights activists for young adult readers.

References:

Gilbert, Elizabeth, Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear, Bloomsbury, London, 2015