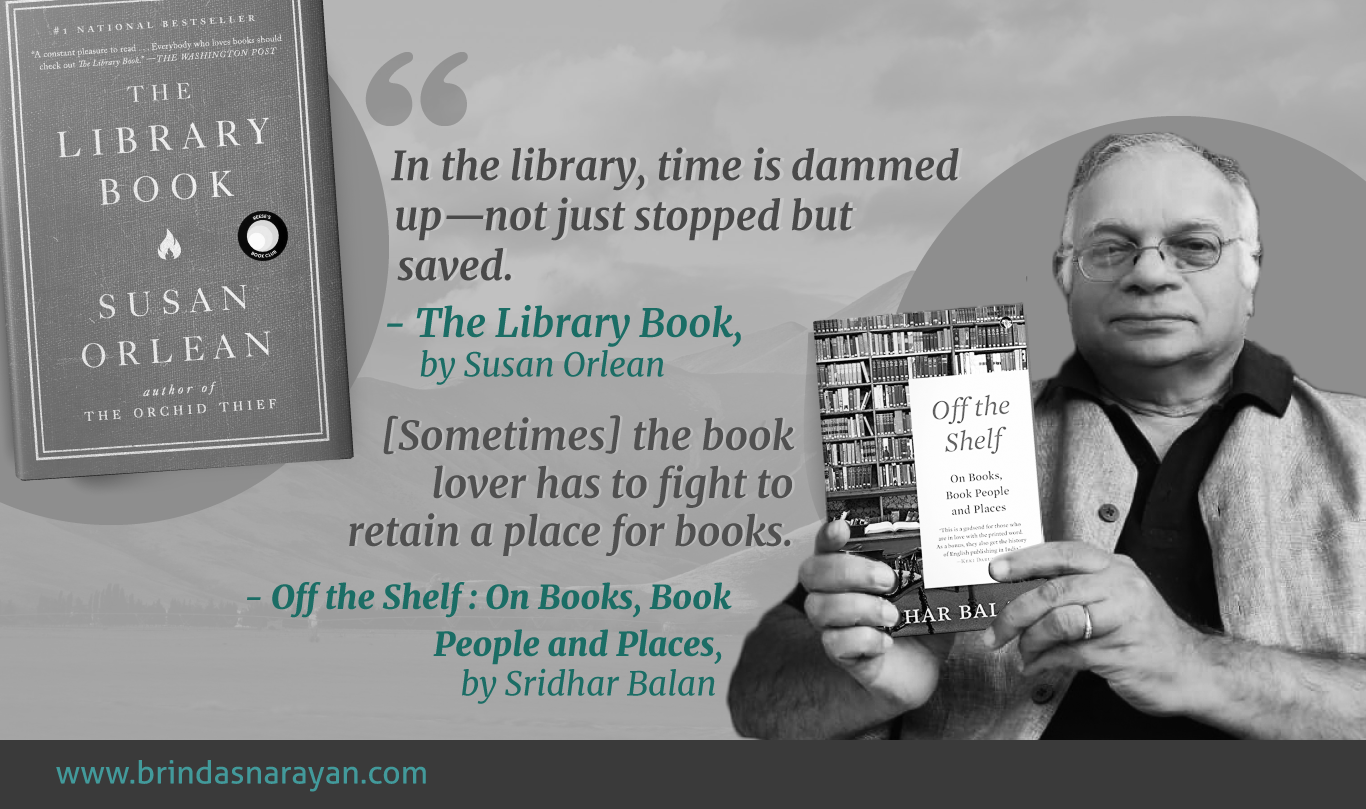

Sridhar Balan, Author, Publishing Veteran and Literary Columnist, Charts A Bibliophile’s Journey

The Library Book: Susan Orlean Recalls an Idyllic Time inside Libraries

Harry Peak was often characterized by his “very blond” hair. Growing up in Santa Fe, not too far from the giddying dazzle of Hollywood, the kid had a flair for theatrics and drama. But his skills often slid into playing the kind of pranks or telling the kind of lies that would garner attention. Later on, as an adult, he told his family that he had landed acting parts in movies, but IMDB credits did not feature his name in any productions. Ironically, he did parachute into fame when linked to a deed his family might have preferred to forget. He was accused of setting fire to the Los Angeles Central Library in 1987, “destroying almost half a million books and damaging seven hundred thousand more.”

In her riveting, The Library Book, Susan Orlean walks us back to those places or times, when libraries nurtured our humanness, and also expanded notions of possibility as our eyes or fingers flickered across book spines. She quotes the writer (and avid reader) Borges, who expressed a sentiment most readers would endorse: “I have always imagined Paradise as a kind of library.”

She recalls a childhood in which much of her time was spent inhabiting a particular public library in Cleveland. It was the first space, where she was permitted “autonomy” and a distance from parental protection. She usually accompanied her mother to the library: “Even when I was maybe four or five years old, I was allowed to head off on my own.” She also remarks, that unlike in visits to malls, where there were inevitable squabbles between the parent and child – with the former wanting to give less and the latter wanting to get more – the library was a “dreamy” and “frictionless” space, where she could make her own book choices.

Off the Shelf: Sridhar Balan Evolves into a Penetrating Reader

In a different part of the world, a young Sridhar Balan, like Orlean, journeyed into textual terrains. Growing up in Calcutta in the late 1950s, in a city built on liquid marshes and salty wet lands, its watery origins obscured by smoky coffee houses and wistful revolutionaries, Balan was often immersed in books. Besides dipping into his household’s library, he fondly recalls participating in another family ritual – oral storytelling and reading books aloud. Since Sridhar’s father lacked the time or opportunity to read between office pressures and other midlife stresses, he requested his oldest daughter Jaya to read aloud her favorites.

Jaya was a particularly captivating reader, and she transported the Calcutta family into Emily Bronte’s savage moorlands or into the sinister and baffling events in Charlotte Bronte’s Thornfield. At that point, the child Balan, always keenly observant, noticed something magical unfold. Despite the session often being interrupted by his father’s trips, the family was hooked by the question that the Bronte sisters never failed to evoke: “And then…?” On his return from his work tours, Sridhar’s father and other listeners would insist that Jaya resume from exactly where she had left off earlier. Predating the contemporary but more isolated act of binge-watching, the family was in thrall to stories, and to their grip on the human imagination.

Later on, such reading aloud was to continue in other languages. Sridhar’s mother read out serialized Tamil stories from periodicals like Ananda Vikatam and Kumudam. In particular, the writer Kalki fostered a zealous fandom in Sridhar’s mother and paternal grandmother, who was rather grief-stricken, when the writer died at a young age. Balan was entranced by the notion that Kalki’s craft “could touch a reader so deeply.”

In the 1960s, Sridhar was sent to a boarding school in Ooty, and among the lush hills and bewitching woods, his enchantment with books only deepened. He won many prizes at school and later on at his college in Calcutta, where he also enrolled as a member of a lending library. Through his later school years and into college, he charted a distinctive reading trajectory for himself, inhabiting, like most readers, parallels worlds that tugged him away from everyday mundanities.

A cherished book gifted to him by a history teacher was Stefan Zweig’s memoir, The World of Yesterday. The book evoked Vienna’s throbbing intellectual, artistic and cultural scenes before the World Wars were to rip through the Austro-Hungarian region, culminating in the author’s own personal and political exile from Europe. Another book that moved him had been gifted to his younger sister, Lalita. The Lenz Papers by Stefan Heym is a work of historical fiction and dwells on the “failed 1848 revolution in the Grand Duchy of Baden.”

Weaving skeins of history with romance, Heym yanked an engrossed Sridhar into a time when Marx and Engels produced their status-tumbling journal and prophesied the collapse of capitalism.

The Library Book: Orlean Rediscovers the Magic of Libraries

Balan, growing up in a period when families were constrained by frugal means, often relied on books borrowed from lending libraries or on book prizes awarded to his siblings and him. Though Orlean grew up in a more consumerized country, her parents, being the offspring of the Depression Era, were consciously thrifty. Hence books were deliberately borrowed rather than bought.

However, as Susan moved to college and beyond, she willfully started buying books, building “a totem pole of the narratives” she had lingered over or skimmed through, highlighted and marked up. Zealously cultivating an identity that was both shaped by but also distinct from that of her parents, she filled her apartment bookshelves with ‘extravagances.’ With a growing home library, she stopped visiting public libraries for a few years.

Much later, when she moved to Los Angeles with her first-grade son, she was compelled to visit a public library. And the past came rushing back to her. In the hush between bookshelves, in the gentle creaks of carrels, in the hum of water pipes, and in reader murmurs, the sounds and deliberate silences of her childhood hurled her back to what felt like a forgotten “country.” She realized why her apartment bookshelves were inadequate. She no longer experienced the serendipitous alighting on a strange title, the seductive invitations of unexplored subjects or authors: “On a library bookshelf, thought progresses in a way that is logical, but also dumbfounding, mysterious, irresistible.”

Off The Shelf: Foraying into the Nation’s Reading History

In his book, Balan draws us not only to the zigzag thoughts engendered by libraries and bookstore nooks, but also into vividly-sketched vignettes from the nation’s reading history. Having held senior positions in some of the country’s most reputed publishing houses, including Macmillan and Oxford University Press (OUP), Balan has not only consorted with many of India’s leading intellectuals – like the sociologists Andre Beteille and Dipankar Gupta, the anthropologist T.N.Madan and many others – but also helped fashion their books and public interactions.

Deftly darting between past and present, Sridhar cites how Macaulay’s much-cited, socially-transformative ‘Minute on Education’ not only spawned a tribe of English speakers in India, but also stoked a demand for English books in the colony. Such thirst for English literature was initially quenched by “journeymen” or “carpetbaggers” – salespersons from the UK, who were quick to exploit the mushrooming market. Slowly, other enterprises started taking root. British publishing firms were the first to set up offices in India, with Macmillan and OUP featuring in the vanguard.

The three earliest English authors promoted in the Indian market include names that are probably unfamiliar to most of us, steeped in the canons of what used to be considered the “classics”. Balan offers a riveting glimpse into the personal histories of the three men who whetted Indian readerly appetites with their swashbuckling adventures or melodramatic mysteries. G.W.M. Reynolds (1814 – 1879), G.A. Henty (1832-1902), H. Rider Haggard (1856 – 1925), were at one time wildly popular in India, even long after their renown had eroded inside the parent country.

Sridhar illustrates the colony’s cultural and literary distance from Britain with a little-known but rib-tickling story. When the author Mulk Raj Anand met Virginia Woolf and wanted to impress her with his literary leanings, he declared that he had assiduously avoided Reynolds’ writing style while shaping his own sentences. Later on, a bewildered Woolf is said to have asked her husband Leonard Woolf, “But who on earth is G.W.M. Reynolds?”

Off the Shelf: Cultivating Young Readers

After his stint at OUP, Balan consulted with Ratna Sagar, an academic publisher, to extend and grow their reach among schools in India. Sridhar realized that as the parental thrust for strong English skills had only heightened with liberalization, he needed to ensure that students read more. Besides, both parents and teachers bemoaned the erosion of the reading habit among kids. Recalling instances from his own childhood, Sridhar suggested that parents create an oral storytelling hour at home. He also persuaded teachers to “act” out stories at school, hence forging the otherwise obscure link between words and actions, while also advertising the lures of the library on school noticeboards.

When Sridhar queried teachers about the presence of books inside their own homes, he found that most of them did not accord a special place to books. While one can empathize with the cramped habitats of those who are socio-economically deprived, he notes that even those who have space for other objects, do not accommodate book shelves.

Off the Shelf: Cherishing Libraries at Home and in the World

As a book lover, Sridhar cannot fathom being distanced from the pages that have drawn him into a plethora of histories and geographies. He cites the story of Alberto Manguel, the author of A History of Reading, among several other works of fiction and non-fiction. The Argentinian Manguel, who also read works aloud to the blind Borges, once shifted from Canada to France, simply to accommodate his growing collection of books. In France, more than the 15th Century Chateau that he and his partner were to inhabit, Manguel obsessed with the barn – a space that was to be dedicated to his 30,000 books. Like Manguel, Sridhar too had to shift to a temporary residence while his home was being redesigned. Like any compulsive reader, he could not imagine his books being stored out of sight during the hiatus.

On Balan’s own book shelves, the books by the Argentinian intellectual occupy “pride of place.” Manguel explores the history of libraries, the manner in which words remake cities (and often, lower violence in places that nurture libraries), and also ruminates on his own ongoing relationship with books. Sridhar also recalls a visit to Manguel’s city, Buenos Aires, as a UNESCO delegate, to share ideas on how to strengthen reading among children. The Argentinian capital also harbors the highest number of bookshops among all world cities, and boasts of the magnificent National Library of Argentina, of which the colossal Borges and Manguel were former directors.

The Library Book: The Fire Rips Through the Stacks

On April 29, 1986, the fire that burned The Central Library in L.A. was hardly a minor one. It raged for “seven hours and reached the temperature of 2000 degrees.”

Yet, the incident hardly received the media attention warranted because at the same time, uncannily enough, a reactor fire had erupted at the Chernobyl nuclear plant. As Orlean puts it, “[the] biggest library fire in American history had been upstaged by the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown.”

When the fire alarms rang out, as they did every now and then, many customers and librarians sauntered out, with their valuables still lying on tables, expecting to come back soon after the false or exaggerated sirens had been silenced. Even when the smoke started curling its ways through and around the library, the spectators outside hadn’t seen any signs for a while. The vapors morphed, as the fire and heat gathered strength: “At first, the smoke in the Fiction stacks was as pale as onionskin. Then it deepened to dove gray. Then it turned black.”

As the fire grew into its third intense hour, the crowd outside the building watched with mounting horror. Librarians wept as sooty pages from recognizable books fluttered towards the pavement. The firefighters “suffered burns” or “respiratory distress so extreme,” they were ferried to proximal hospitals for immediate attention.

The total volume of books burnt by the fire was estimated at 400,000. Above that, 700,000 books were mutilated by smoke and water. “The number of books destroyed or spoiled was equal to the entirety of fifteen typical branch libraries. It was the greatest loss to any public library in the history of the United States.”

The next day, more than 2000 volunteers, most of them ordinary citizens, helped rescue whatever they could of the remaining books. Wet books were carted to freezers across the city to prevent mold from feeding on their innards. Books were stored inside grocery outlets and in fish processing units, demonstrating the ingenuity of the human spirit when confronted with a crisis. Volunteers worked for three full days and nights, forming a “human chain,” where kind and committed strangers passed books from hand to hand. “They created,” Susan says, “for that short time, a system to protect and pass along shared knowledge, to save what we know for each other, which is what libraries do every day.”

The Library Book: Harry Peak is Discharged

Harry, like many of the other desperate young men who flock to Los Angeles because they think they possess an elusive “star quality,” aspired to be an actor. He clearly sought the attention and glitz of such a job. But however extraordinary he might have felt in Santa Fe, he was remarkably common in Los Angeles. As Orlean observes, “The sidewalks in Hollywood sagged under the weight of all the handsome young men who flocked there…”

Later, however, arson investigators, despite strongly suspecting Harry of the crime, could never really get the charges to stick. There wasn’t enough evidence that he had done it. More recent investigations into the incident wonder if the fire might have erupted accidentally – sparked by a faulty wire, a tea kettle, or some other undiscovered cause obliterated by the flames. Peak, himself, died tragically of HIV, his Hollywood dreams unfulfilled.

The Library Book: Entering a Reader’s Dystopia

In Ray Bradbury’s memorable Farenheit 451, Montag is a fireman who is ordered to burn books inside a regime that has outlawed reading. On the sly, he starts saving a few books and reading them. He discovers the wizardry and power of pages. Just then, his wife squeals about his activities to the Authorities, who try to murder him.

He escapes the city, and meets a tribe of impoverished misfits, bibliophiles who are softly quoting snatches of Shakespeare and Proust, among other classical works. He realizes that they are consciously memorizing the contents of books in order to pass on their knowledge to future generations as oral storytellers.

It’s a form of transmission that Sridhar Balan champions, to save future generations from the distracting seductions of devices, and even perhaps, from themselves.

References:

Balan, Sridhar, Off the Shelf: On Books, Book People and Places, Speaking Tiger, Delhi, 2019.

Orlean, Susan, The Library Book, Simon and Schuster, New York, 2018.

Just a random thought.Alexander had the library at Persepolis burnt to take revenge. ..must have been the prized possession of the Persians.The power of the written word is strong indeed.

Waiting to get my copy of Sridar Balan’s book.