Reimagining Riverine Histories

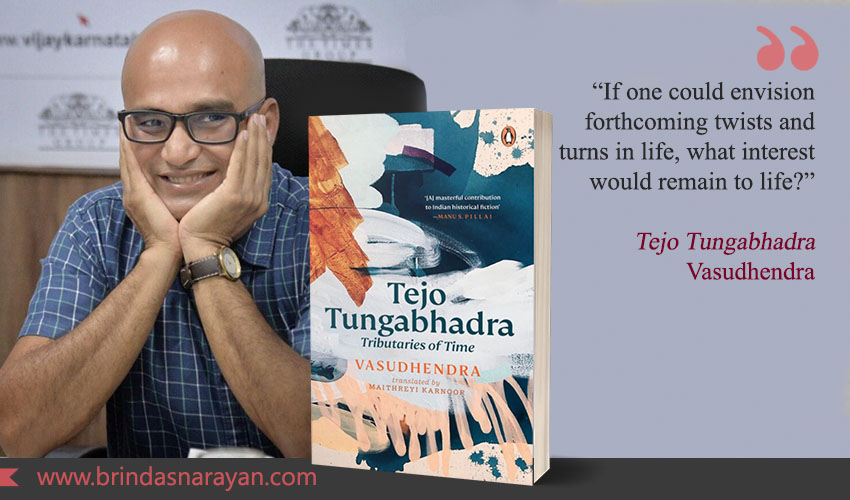

Tejo Tungabhadra, written originally in Kannada by the versatile Vasudhendra, and translated deftly by Maithreyi Karnoor, brings to life a glittering panoply of 15th and 16th Century characters. Yanking readers into times when Sati was not just thrust upon Indian widows but fiercely celebrated, when the heretics of one religion were decapitated by the believers of another, one realizes that history often circles back to the present, with frightening reminders of the barbarity inherent in all societies and cultures.

This is a deeply-researched and towering work that reinforces how stories are like rivers. With each originating at different sources, but capering through landscapes with twists and bends, occasionally halting in lake-like pauses, before leaping into torrential waterfalls or monsoon-drenched floods.

More terrifying than the blues of the river, are the blues of the ocean. When Gabriel, a Portuguese scribe who has signed up to voyage to India to make his fortune, stares out at the vastness around him, he’s understandably overwhelmed: “There is nothing but blue for as far as the eye can see: sky blue, ocean blue, eye blue – it is the combined blues of the sky, water and the soul’s abyss.”

Witnessing Spicy Love

Starting out in 15th Century Lisbon, by the river Tejo, the novel begins with the seemingly forgettable. With a fugitive woman being killed. Her bloodied corpse is left to rot while palace guards pick through her bundle and clothing for spices. For the faintest dregs of pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, for aromatic whiffs that count for more than a human life. Such greed was seeded by Vasco de Gama’s discovery of India, by his violent plunders of coastal riches that led to the carting back of spices, ivory and silks to King Manuel of Portugal.

Before spices, other human appetites were whetted. Like the forbidden love between Bella and Gabriel, one a Jew, the other a Christian, one rich, the other poor, one a migrant, the other a native. Tejo (the river) watches them come together and split. Or temporarily detach themselves while committing to an imagined, future reunion.

The Struggles of Faith

Bella’s family, with other Jewish compatriots, had been driven out of Spain by Queen Isabella. They landed in Portugal, to rebuild their lives and fortunes from scratch. The Jews, soon enough, had settled in the new country, while establishing businesses that boosted the economy. Bella’s father, Belsham, started a printing press.

Gabriel’s father, Antonio, was a poor sculptor. He fashioned stone pillars to plant in foreign lands, and establish the Portuguese dominion over those places. Antonio respected Belsham for his industry, wisdom and business acumen. Till the tables were turned, and the Jews were forced to convert to Christianity, swearing their allegiance to their adopted nation’s religion. When thousands were lined up to be forcefully baptized, a few young men started reciting their Jewish prayers. Their heads were promptly lopped off, compelling the others into a frightened and resentful acquiescence.

When a hopeful Gabriel asks Belsham for his daughter’s hand, the rich but bitter father, still smarting from his forced conversion, reminds him of the impossibly high bride price. A humiliated Gabriel sets sail to India, a voyage fraught with unimaginably harsh conditions – starvation (there are times, when the imprisoned sailors realize that rats are tastier than nothing), water deprivation, and other forms of torture magnified by rollicky seas.

Tales Along Tungabhadra

Across the ocean, the River Tungabhadra witnesses other stories – when Vijayanagara was ruled by Krishnadevaraya. The drama unfolds in the smaller town of Tembakapura, where harsh gossip and brutal traditions rein in personal liberty. Unlike in Portugal, where the same spice is treated like flecks of gold, plentiful peppercorns are flung about during a temple procession. The cultures and social practices are different. So are the languages and religions. But the same human emotions rule: Hampamma and Keshava are in love, but the married Mapala also seeks her hand. Fighting each other to death in a wrestling duel, the winner does not feel as jubilant as he had expected to. And neither does Hampamma, whose victorious husband turns less trustworthy with time.

Intertwined Histories

Shifting back and forth between continents and across the tides of history, Vasudhendra painstakingly shows how larger forces impinge on smaller lives. Though depending on where you shine your lens, no life is small after all. Every character embodies a world – of love and lust, ambition and betrayal, jealousy and deceit, fear and guilt – and no one can elude the bittersweet ravages of time. The ruthless Alfonso Albuquerque conquers Goa for the Portuguese but the locals – whether Muslim, Hindu or Christian – could have hardly claimed the moral higher ground. Before there were foreign conquerors, there were internal divisions. As the author puts it: “Human beings it seems are restless when there is no one to hate.”

That, unfortunately, with all the battles currently raging, seems like an adage that still holds true. If only we could attend to the author’s deeper message: “God is not someone who sits in the sanctum sanctorum of temples. He walks among us. What we need is the perception to see him.”

References

Vasudhendra, Tejo Tungabhadra: Tributaries of Time, Translated by Maithreyi Karnoor, Penguin Random House India, 2019

Thanks Brinda. You have so nicely captured the essence of the book. Your observations are apt and accurate.