Snigdha Poonam: Charting a Dream Career from a Journalist to an Acclaimed Author

For a particular writing project, I needed to understand how small towns in India were getting transformed by the forces of late modernity and conspicuous materialism. While Bollywood was both plying and shattering conventional notions in movies like Bareilly ki Barfi and Masaan, I was looking for an updated version of Butter Chicken in Ludhiana, Pankaj Mishra’s snapshots of his meanderings across small towns in the mid-90s, soon after liberalization had ushered new cultures across our borders.

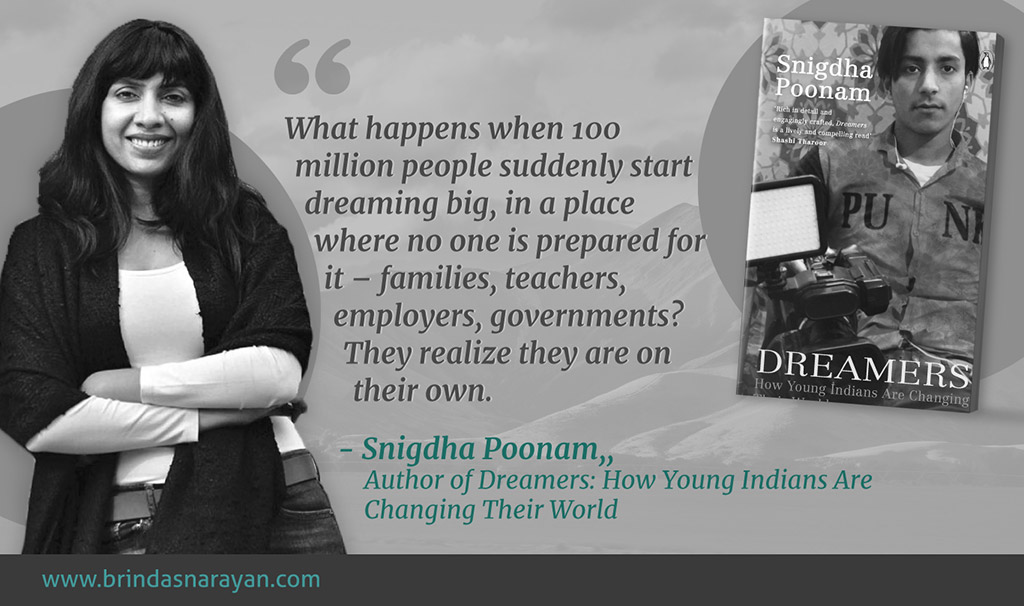

A quick internet search landed on Dreamers, a book that had created a significant flutter among Indophiles. Moreover, the work had received strong acclaim from national and international media, including The Guardian, The Economist, The Wall Street Journal and The Times Literary Supplement, to name a few. Sunil Khilnani, the historian and author of The Idea of India, characterized it as “a brilliant dive into the seething psyche of India’s small-town youth.” Other intellectuals like Mukul Kesavan, Shashi Tharoor, Mrinal Pande, Pankaj Mishra and Jason Burke were equally unstinted in their praise.

It’s not easy for most authors to deliver on raised readerly expectations. Yet, when I started immersing myself in Poonam’s intensely gripping and deeply unsettling account of surging ambitions, of dreams fulfilled or heartbreakingly deferred, entering into the kaleidoscopic lives that animate her book, I found myself in a position that readers yearn to occupy, but are rarely granted: I couldn’t stop turning the pages.

From The Dreamers: WittyFeed Spawns Viral Content

Engendering addictive content was also the objective of WittyFeed, an Indore-based company that was once valued at an astounding $30 Mn.In May 2016, Snigdha travelled to the densely-populated city to hang out with the team that created snappy, clickbait content. Scanning the landscape in her new destination, she noticed consumerist longings flicker across hoardings and sign boards. Of course, this being India, the old and the ever-extant jostled with the new: “Cool coffee shops are coming up on cow-populated lanes.” Moreover, the internet was spreading its identity-scrambling tentacles into small-town alleyways: “Youngsters wander its streets in Instagram-ready outfits.”

Inside the WittyFeed office, employees were surrounded by the seductive lures of American success. The office radiated the Silicon Valley’s curated casualness in its bean bags and ping pong table, amidst posters of the Grand Masters of Contemporary Cool – Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, brushing with cheerful disregard against historical greats like Abraham Lincoln.

Snigdha, who had been a journalist at publications like The Hindu and The Caravan for many years, witnessed an editorial meeting like no other. Ideas at WittyFeed were approved or abandoned at lightning-speed. It wasn’t just the quickfire decisions that separated the editorial huddle from others. It was also the startling, jarring fact that a bunch of very young Indians from small towns and villages, were dispassionately and successfully spawning outlandish headlines to lure millions of American readers, stories with the one attribute that internet content producers most desperately seek: virality. “Fifteen minutes is all it takes the team to go over the whole range of American obsessions, from Kardashians to belly fat, from sex confessions to life hacks,” Poonam says.

One of the criteria to enter the company was that you must really “want it bad.” The employees lived together in two bungalows and were asked to regard each other as “brothers” and “sisters.” As Snigdha astutely observes, for many of the young Indians entering the interview, this was the first time ever in their lives, that they were being asked to define themselves. “In a society where who you are – caste, class, region, religion – is decided for you long before you are born, ‘wokeness’ is a luxury.” But getting from such awakening to suddenly shaping ideas that stirred readers in other continents seemed to occur swiftly: “A week at the company is all it takes them to go from not knowing anything about the world to deciding what the world should know.”

An 18-year-old from Indore who had never been on a date soon advised Tinder users on ‘bread crumbing’ – the apparently artful act of sending “flirty yet non-committal texts.” One of the company’s memorable successes dwelt on an existential question that occurred to the company’s CCO, while on a flight. The story titled, “What Happens to your Poop in an Airplane Toilet Will Leave You Surprised,” garnered an eye-popping 315,000 views. Emerging from households where the sheer idea of a pool was inconceivable, the high-spirited and resolute creators at WittyFeed reassured foreign readers that “This Man Couldn’t Afford a Swimming Pool but What He did Next is Truly Fantastic.”

The founder of the company, Vinay Singhal, liked to think of himself as someone gripped by “madness” – a raging desire to grow rich, and then to take over the nation and run it with the kind of frenetic efficiency that powered WittyFeed. Singhal believed that Indian hunger forged with age-old family values could trump the West at its own games.

Snigdha Poonam: Finds Dreamers Everywhere

Such “hunger” – not just for food, a house and car, but for immense riches and immeasurable fame seemed to abound in small towns, across many of the young people who constituted what the country construed as its “demographic dividend.” As Poonam puts it: “They see no connection between where they live and what they want from their lives.”

Many years ago, the Kannada writer U.R. Ananthamurthy had used the term “antinomies” to describe an India that inhabits many centuries at once. Unsurprisingly then, the smalltown Gen Zs and younger cohorts resided among the contradictory tugs of the old and new. As Snigdha says, they possessed the “cultural values of their grandparents – socially conservative, sexually timid, God fearing – but the life goals of American teenagers: money and fame.” Unlike Poonam’s own peers, large numbers in the new generations seemed to harbor gargantuan dreams. While she continued to be amazed at how rapidly the region had evolved, she was also awakened to the fact that many places she had once called “home” held startling unknowns.

Snigdha Poonam: An Intensely Bookish Childhood

Born in the early 80s, Snigdha grew up in remote, isolated “blocks” in the then combined state of Bihar, before its southern portion had been split off into Jharkhand. Her father worked in the Civil Services, and the family was hence subjected to frequent and capricious transfers. With her school years spent in such a shifting landscape, proximal to villages and unknown, tiny towns, she bore the costs and reaped the gifts of an isolated childhood. While she played with the kids of other civil servants and some school friends, she had no means of entertainment or stimulation, apart from books. As Poonam recalls, “there was nothing else to do but read. There was often no electricity even to watch TV with.”

But it wasn’t just the confinement that turned her into a prodigious reader. Both her parents read widely. She watched her father spend all his non-working hours with books, transposing himself from his spartan Bihari life into Thomas Hardy’s Wessex or Charlotte Bronte’s stormy moorlands. Her mother, who was also engaged socially with local communities, immersed herself in the riches of Hindi and Urdu literature, drawing Poonam’s attention to Munshi Premchand’s evocative sketches of peasant life, Shivani’s sensitively drawn Kumaon women or Ismat Chughtai’s feisty feminism. Because of her parents’ strong but also distinctive literary influences, Snigdha grew up reading extensively in both languages. But ushering in as well the chutzpah of a younger generation, she was “rather indiscriminate in her reading,” soaking up everything, ranging “from the Classics to true-crime tabloids.”

Unsurprisingly, she evolved into a “very precocious child, curious and fascinated by everything.” When she was entering the 9th Grade, they moved to Ranchi, the biggest city she had lived in till then and where she completed the rest of her schooling. In the earlier classes, she often had to switch between Hindi medium and English medium schools, becoming as a result strongly bilingual. But she also perhaps developed a kind of fortitude, with the school changes imposed on her at unpredictable intervals, sometimes in a span of a few months or sometimes after a few years. This might have imbued her later with the steely courage to pursue her stories in remarkably high-risk spaces.

Snigdha Poonam: Propelled by Middle-Class Expectations

Entering the 11th Grade at the Kendriya Vidyalaya in Ranchi, she was tugged by typical middle-class Indian expectations. While she always treasured her time with books and literature, she fell into the grooves imposed on bright kids. Since she wasn’t inclined towards Engineering, she attended coaching classes for Medical entrance exams. Being perhaps, only partially inclined towards Medicine and given the unevenness of her early schooling, she wasn’t admitted into medical colleges. But the family’s emphasis on pursuing some “Science” subject drove her to a college in Hyderabad, for a degree in Agricultural Sciences.

At college, Poonam remembers being starkly demotivated. Clearly, the subject wasn’t one that drew her interest. In the meanwhile, she found herself enthralled by “news” – by larger political and social currents that were reshaping a liberalized India and the world. During her first year in college, she watched 9/11 unfold. Even as her attendance at her Agricultural courses plunged from desultory to abysmal, she was riveted by the manner in which the distant implosion rippled across borders. Though her teachers urged her towards lucrative fields like Biotechnology, she knew by then that she was “progressively more and more miserable with her academic path.” Fortunately, at that point, she decided to break away from mainstream careers. She had also observed that many journalists in India had landed in the field after failing to break into Engineering, Medical or Civil Service careers: “In India, you have to try to do everything else first, before you become a journalist.”

Snigdha Poonam: Identifies and Pursues Her Interest

As a teenager, Snigdha had already started submitting stories to teen pages in various publications. After her college degree, she was certain that her interest lay in news and writing. Since her English had already been honed by her extensive reading, she easily passed the test at The Hindu, where she joined the Bangalore office as a copy editor. Along with her desk job, which involved rewriting stories on a late-evening shift, she also persistently pitched stories to various pages. Leveraging her internal connections with various page editors, she landed many writing assignments covering theatre openings, press conferences and other events.

But she had always been a keen reader of magazines. Even at Bangalore, she continued to haunt bookstores, including the historical Select Bookshop on Brigade Road, that had drawn eclectic scholars and writers like Ruskin Bond, Ramachandra Guha and Girish Karnad to its shelves. Here, she bought up a variety of literary magazines, including The New Yorker and The Caravan. By then, she was also reading material online, tuning herself to the mechanics and styles of long-form journalism and in-depth reportage.

Keen to expand her own journalistic experiences, she applied to The Caravan, and began working inside a magazine that spotlighted the country’s socioeconomic crevices with carefully crafted, deeply researched narratives. Starting out at the magazine as a copy editor and then growing into an assistant editor, she also wrote as extensively as she could. She expanded her repertoire to include perspectives and profiles. She recalls the training she received at The Caravan with gratitude, where she was exposed to “big name” writers and prominent thinkers like Panjak Mishra and Ramachandra Guha at in-house workshops and discussions: “I developed a lot during the four years there.”

Snigdha Poonam: Unearths “Riches” in Small Towns

During her time at The Caravan, one particular story not only left a deep impression on her but also ended up reshaping her future. The year was 2010, and the idea of online dating had just entered the Indian market, luring its largely-timorous youngsters with partners on tap. Curious about how such a phenomenon would take root in the Indian environment, Snigdha suggested to her editor that she sign on as a user and explore her own experience. Having already attuned herself, as a reader, to the appeal of first-person reports, she sensed that such a story would be served best by an immersive viewpoint.

After setting up an account on one of the dating platforms, the next morning Poonam was taken aback by the sheer deluge of young men who wished to connect with her: “All kinds of people from the smallest towns and villages wanted to talk to a woman. They started to tell me all about their lives.” While some men were expectedly sleazy, many she realized were just eager to talk. Reflective perhaps, of the isolation and awkwardness fostered by gender segregation norms that still prevail in many sections of the country, the online platform represented an opportunity to mingle with the opposite gender without the eyes of a whole village or town trained on their interactions. Poonam noticed that for many respondents, the sheer act of talking to a woman, and equally perhaps, of having someone listen to narratives of their lives was new to them.

Snigdha realized that inside her own sheltered upbringing, she had only scant knowledge of the young men who inhabited the Hindi heartland. The dating story led her towards other equally interesting aspects about small town youth. She was also, perhaps, one of the few English-media journalists who was specifically focused on social and cultural shifts inside the nation’s largest vote bank: “I realized that I had found this goldmine.” At that point, she also started contributing a column to The New York Times, charting changes in youth culture. One story focused on personality development classes, while another dwelt on the young authors who were reshaping small town imaginations.

Around then, at a party in Delhi, she encountered Chiki Sarkar, the then Managing Editor of Penguin India, who suggested Poonam follow a particular set of people in small towns for a year and write a book. Inspired by Sarkar’s suggestion, Snigdha embarked on a sabbatical. Even before setting out on her research, she was clear that she wanted to follow people with “big dreams.” As a veteran reporter, she knew that characters needed strong internal drives to propel their stories forward. She also planned to use Ranchi as a backdrop for all her narratives. When she landed in the city where she had spent all her high-school years, she found the place starkly different from the one she recalled.

But the other surprising aspect was that she thought she would have to struggle to find the kind of people she was looking for. She says, “instead I found them everywhere.” She would hang out at the usual places that young people inhabit, like coffee shops, college cafeterias, coaching classes and she would frequently encounter kids who no longer seemed to have the kind of ambitions she had at that age. Many in the new generational cohorts seemed to harbor immense ambitions.

From The Dreamers: Moin Khan Masters English

One of the dreamers was a young man called Moin Khan. At 17, he was a balloon seller in his Jharkhandi village. Then in 2004, the Natural Creative English Vision set up a center in Khan’s village, which was not too far from Ranchi, but “100 years in the past.” This was during the period when call centers were mushrooming in the country, and the demand for English speakers spreading into B-cities, small towns and villages.

Khan, who entered the English class in his village with great temerity, was completely taken in by his teacher. Moin decided that he wanted to be exactly like him. The class required all participants to offer a brief introduction to themselves. It took Khan nearly 11 days to summon the courage to stand in front of his village peers. It wasn’t so much his inadequacy in English, but an internalized sense of his own “level” in the village. He felt like the room could sniff out his inferiority, as easily as they could inhale the whiffs of cow dung that clung to his body.

Such diffidence about his own standing also masked a deep yearning to alter his circumstances. For the next six months, Khan stopped sleeping and drove himself relentlessly, determined to master English at any cost. Every night, notebook in hand, he repeated every single word and phrase his teacher had uttered in class – mimicking everything, the tone, the inflections, the tiny behavioral nuances that distinguish the ‘polished’ from the ‘uncultivated.’

At the end of such a punitive regime, Khan had mastered the rubrics of English, enough to stand before the class and announce: “Good morning to all. It’s a gala day for me.” However, Moin wasn’t satisfied. He knew his sentences sounded scripted and faltering, not flawless like his teacher’s. He sensed that he needed more speaking practice than the classroom allowed. So, he persistently dialed 121, the telco provider’s free customer service line, and repeatedly spoke to customer service agents who were occasionally willing to tolerate his monologues. But even that wasn’t enough. He gathered his close friends in the village, and forming a circle above a river’s waters, he vowed that they would speak to each other only in English for a month. At home, too, he stopped speaking to his family in any other language.

Witnessing Khan’s painstaking exertions, his teacher asked him to become the Center’s next teacher. Moin was aghast. Embodying the pathos that encodes social divisions in India, Khan told Poonam: “I was the same person who dispatched milk to their houses in the morning – ‘this gwala (milkman) will teach us English’ – they would say the moment I stand before the class!”

Ten years later, at 27, when Snigdha encountered Khan at The American, a spoken-English center at Ranchi, he exuded the very quality that he once tried so hard to consciously imbibe: “cool.” As the trainer of a nervy, English-seeking batch, he consciously dressed and groomed himself with seemingly casual swagger: T-shirt, linen trousers, pointy-black shoes, French beard. Even now, whenever he returned to his original village, he was urged by disbelieving but proud neighbors to say something, anything in English: “Kuch bol ke sunao na.”

Snigdha Poonam: Cautions Writerly Aspirants to be Prepared for a Slog

Like Khan’s hard-won transformation, Poonam’s own journey from her relatively protected childhood, mostly spent in the spent in the boondocks of Bihar and Jharkhand, can be galvanizing for young people who wish to break into the clubby world of narrative non-fiction writing.

But like with any other publicized success, the end-result was achieved only after crossing significant, often heart-stopping hurdles. During her research, she inevitably encountered obstacles. For one thing, she often had to maneuver her schedule to be physically present during major life changes or certain events in her subjects’ lives. She also found fewer women willing to open up, since they often required permissions from male members in the family like brothers and fathers. Also, though some interviewees had accorded access earlier, they withdrew later – for instance, after getting married.

In the midst of the project, she ran out of funds, and needed to do other assignments to finance her journey. She then decided to expand her stories outside Ranchi, since many of the other cities like Indore and Allahabad were also spawning young, “big” dreamers.

While working on a new narrative nonfiction project, she warns aspirants to the terrain, that they shouldn’t hanker to see their names in print, before putting in a lot of the grueling grunge work that goes with desk jobs or other aspects of the media business. She says, “Bylines often appear only later, after a few years on the desk.” Moreover, she also urges them to hone their writing and research skills, developing “empathy, patience and perseverance,” rather than shooting straightaway for fame and riches.

References:

Poonam, Snigdha, Dreamers: How Young Indians are Changing Their World, Penguin Random House India, Delhi, 2018.