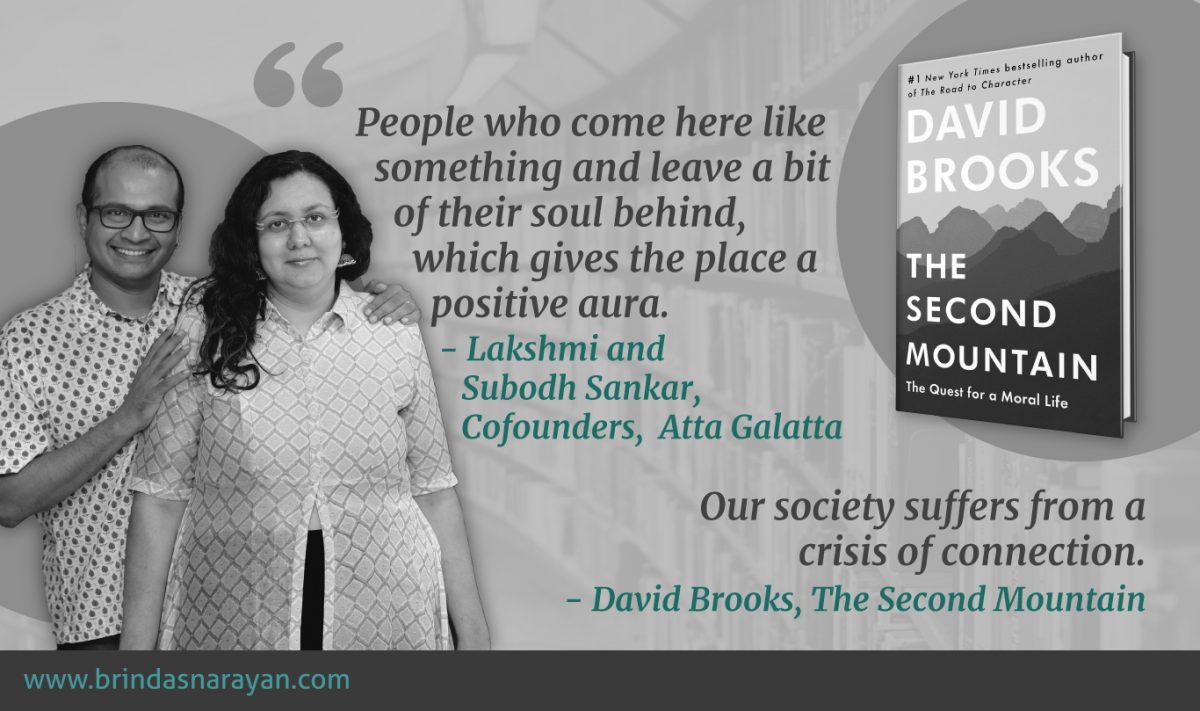

Climbing the Second Mountain: Lakshmi and Subodh Sankar, Founders of Atta Galatta, Create a Storied Bookstore

David Brooks: Embarking on a Personal Quest After a Divorce

In The Second Mountain, David Brooks, acknowledges with a beguiling honesty, that at the age of 52, he felt suddenly unmoored. His three-decade long marriage had ended, and he was “lonely, humiliated, scattered.” For someone who possessed all other markers of social success – his job and reputation as a New York Times columnist, wealth, kids, a house – the extent of his despair was surprising. Researching and writing a book on midlife transitions was as much a personal quest, an attempt to help himself while also sharing his insights with others.

Examining why contemporary material lives can feel inadequate, Brooks plumbs the social origins of our consumptive culture. As recently as the 1950s, even cities like Chicago wore a different character. Inhabitants were stitched more intimately into communities. Rather than ambition and self-centeredness, a different set of traits were valued. These included “humility, reticence and self-effacement.” Of course, those times were not idyllic by any means. For instance, sexist and racial prejudices were explicitly woven into the social fabric.

Then the 1960s rolled in, with the upheavals that ushered in an era of greater personal freedom. While many necessary rights were wrested from previously oppressive systems, this also led later to hyper-individualism, a framework that persists today in most modern societies. Current norms that value individual autonomy and self-expression also rank people merely by their achievements rather than by their contributions to a family, community or cause. The idealistic 60s have morphed into a belief in consumerism as a form of therapy, and a “preference for technology over intimacy.”

Lakshmi Sankar: A Childhood Shaped by Books

The thrills of a shopping mall or the allures of the internet were unheard of during the childhood of Lakshmi Sankar, a co-founder with her husband, Subodh Sankar, of the iconic Atta Galatta bookstore in Koramangala, Bangalore.

Till the 7th Standard, Lakshmi spent her 1970s schooling years in Mayavaram (currently known as Mayiladuthurai), a town in Tamil Nadu. Though officially inducted into an English-medium school, she grew up in the vibrant environs of tongue-twirling Tamil sounds. With few other distractions in the house – “a courtyard, a backyard well, a lemon tree and a few plants”- she was lured by her father’s books. She read voraciously in both English and Tamil, ploughing through the Katie series (“What Katie Did,” “What Katie Did Next,”), Heidi, abridged editions of Dickens’ novels, Perry Mason and Edgar Wallace. Encouraged by her father to read widely and indiscriminately, she read “all the books [he] was reading too.”

But in the 8th Standard, she was suddenly shifted to a school in Ooty, where she felt like a cultural misfit. “I dressed very weirdly, pulled my socks up to my skirt, wore two plaits with ribbons, was clueless about Michael Jackson and Gloria Estefan.” Her retreat into books became a redemptive bridge to the past. Enrolling at a library at Charing Cross, Ooty, she continued to burrow herself inside magical pages: “I was a very lonely kid, hardly interacted with others,” she says.

It wasn’t surprising then, that she opted to pursue a degree in English Literature at Ethiraj College in Chennai. After college, though she transited into pragmatic jobs in advertising and insurance, she remembers always wanting to start a bookstore. After all, books had always been a lifeline for her, befriending her in the absence of culturally-attuned companions, yanking her from the unbearable stillness of small-town everydays.

The Second Mountain: Initiations Into a Vocation

Brooks remarks that such childhood “annunciations” or initiations into a future vocation are common among those who pursue a calling. Like Lakshmi, many have vocations calling out to them during their youth, but they ignore the summons for financial or social reasons. And later in life, when they’re more secure or unfulfilled in other careers, they return to such pathways.

For others, however, the childhood calling is compelling enough to force an early decision. E.O. Wilson’s parents had announced they were getting a divorce, and they sent the seven-year-old Wilson to stay with a family of strangers, for one summer. During that time, he spent much time on a beach, gazing into the sea waters. He was fascinated by the creatures he encountered there: jellyfish, giant sting rays and crabs. It was an introduction to his future, because Wilson would grow up to be a world-renowned Naturalist. According to Brooks, usually such initiations involve some loss and gain. Wilson’s parents’ divorce was a loss, but the magnetic suction of the natural world was a gain. Lakshmi, too, withstood the loss of empathetic friends to gain a deep affinity with books.

David Brooks: Meets with Uncelebrated but Joyful Doers

Such a strong sense of purpose does not come to all. On his journey, David met with people who were fortunate enough to have stumbled on such callings and seem to exude joy. He observes that they are often people who live for a cause larger than themselves – whether that purpose is the family, community or an idea/movement. “They know why they were put on this earth and derive a deep satisfaction from doing what they have been called to do.”

Many find such personal satisfaction after climbing the “first mountain” – which involves creating a distinct identity and achieving success in social terms, acquiring a car, a house, and a family. Some reach the acme of such a mountain, and then find that success feels disappointingly empty. Or not nearly as fulfilling as it is set out to be. Others are forced to live with mountains of lower heights or with bizarre shapes, when beset by failure in one dimension or another, like a divorce or a job loss. Still others are knocked off the mountain entirely by a catastrophic event, into the “valley of bewilderment and suffering.”

While such times expose the rawest and most vulnerable parts of ourselves, they are, according to Brooks, an opportunity to plumb the depths of our being. While some people might crumble at such times or turn into embittered souls, others discover the capacity to transcend themselves and to care for others.

The Second Mountain: Using Despair to Transcend Earlier Goals

People, who have been through pain or extended despair, start questioning the ideals they set up for themselves earlier. They no longer care about climbing pinnacles they were reaching for at one time. They also rebel against mainstream norms. They are less interested in material goals like money, fame and status. Instead, they move from being “self-centered” to “other-centered.”

In their book, Practical Wisdom, Barry Schwartz and Kenneth Sharpe, relate a story about a janitor called Luke, who was assigned to cleaning hospital rooms. For six months, he had watched a father patiently wait by the bedside of his son, who had fallen into a coma, to awaken. However, so far, there had been no signs of consciousness. One day, when the father had stepped out to smoke, Luke cleaned the room. Later, the father chided him for not cleaning the room. Luke could have instinctually retorted: “I did, when you stepped out.” Instead, he cleaned the room again. Luke had defined his job and purpose as calming patients and their families, instead of just cleaning rooms.

Subodh Sankar: Transits from Entrepreneurship to Co-Founding a Bookstore

Long before he met with Lakshmi, Subodh was already an avid reader. Inspired by a maternal grandmother who pursued a Master’s in Hindi as an adult learner, and encouraged zealous engagement with the world and books in her progeny, Subodh spent many days at the Central Library in Coimbatore. Moving on from his bookish childhood – he recalls being Member #7 at the Tyagu Circulating Library, where he vied with peers to fill up his card at a rapid pace – to cosmopolitan Manipal, for his Bachelor’s in Engineering, and then to North Carolina for his Master’s, Subodh continued reading in both Tamil and English.

Later, tapping into his entrepreneurial bent, he eschewed secure jobs to start his own venture. He sold his first company just before the dotcom bust and then teamed up with others to co-found July Systems. As a pioneer in mobile internet applications, July Systems was lauded for its avant-garde vision. At a rather young age, Subodh had already climbed his first mountain – married Lakshmi, parented a daughter, and successfully co-created an acclaimed technology enterprise.

In 2007, knowing that he enjoyed creating businesses more than working for established ones, he quit July Systems when the company had 250 employees. For a few more years, he continued to assist technology teams, including an incubation hub in Singapore. But by 2011, he felt he was “done with the world of technology.” Sankar says, “I had also grown skeptical by then. I had started wondering, do we really need Facebook at all?”

Struck by deeper questions about the rippling effects of his work, Sankar planned to take a break from his technology career. He told his wife, Lakshmi, that he just wanted to play golf. Such retreats into sports, or into natural environments are often a necessary withdrawal from mainstream pressures, especially when contemplating next steps. In Backpacking with the Saints, the author Belden Lane says that when we retreat into the wilds, there are no people to please and no audiences to applaud you. You can drop all pretenses. You are reduced again, into an insignificant nothing, from which you emerge a healthier person, when you return to your community.

But Subodh did not take the golfing break. Lakshmi, who still harbored her one-time wish to found a bookstore, suggested that Subodh partner with her. Ignoring the warnings of friends and well-wishers, who observed that most bookstores were downing shutters, and despite the looming largeness of online competitors like Amazon, they repurposed their house in Koramangala to accommodate the enterprise. With a keen sense that people wouldn’t be lured merely by books, they recast their place as a platform for creative artists of all kinds – theatre folks, literary authors, storytellers, performing poets and others. Subodh was also keen on fostering a democratic, egalitarian environment that treated both a nervy 16-year-old poet as well as a big-name author on the same terms. “We believe in breaking down walls,” he says.

The Second Mountain: Acquiring Mastery Like Bruce Springsteen

When choosing a vocation, Brooks suggests you pay more attention to what interests you, rather than to the talents you already possess. After all, if you are deeply interested, you will be willing to pour in the requisite time and effort to build talent, and also endure the hardships that accompany callings. In his book, Mastery, the psychologist Robert Greene says that “your emotional commitment to what you are doing will be translated directly into your work.”

Such emotional investment is apparent in the lives of many high achievers, including the iconic singer Bruce Springsteen.Springsteen grew up in a very poor household, where they had to physically lug hot water from the kitchen to the bath tub. At a young age, he encountered Elvis Presley on television and was mesmerized that someone could be having so much “fun” while pursuing a career. He bought himself a guitar and tried to teach himself the instrument. But he soon found it too difficult and gave up. Later, when he encountered the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan show, he was hypnotized again. He bought one of their albums, and started practicing more intensely on the guitar. He often stayed up whole nights, trying to get a tune right, though his fingers became severely callused.

He started a band with some mates in New Jersey, but also knew that he needed enormous self-discipline to drive the team in the right direction. Even, when he had started performing successfully at concerts, he avoided the typical rock star lifestyle, and opted to return alone to his hotel room, with just French fries and chicken, a book and TV for company. In his book, Born to Run, Springsteen says art is a “con job.” “It’s about projecting an image of a rock star, even if you don’t really live it.”

Atta Galatta: The Burgeoning of a Couple’s Passionate Interest in Books and Culture

Like the passionate Springsteen, both Lakshmi and Subodh cherished books and languages. Moreover, both were bilingual readers, as familiar with the Tamil authors, Kalki and Sivasankari, as they were with Arundhati Roy and Amitav Ghosh. Since they tapped into a deep reservoir within themselves, it’s unsurprising that Atta Galatta, with its twisty brick pillars and wooden flooring, its inviting tables and caffeine whiffs, radiates a warmth and energy that’s uncommon among commercial sellers.

Like other givers, that Brooks cites in his book, the couple gives generously of themselves and their space. One of their purposes, as a bookstore and literary space, is to promote regional Indian authors (as well as Indian English authors). They realize that the commercial enterprises typically push well-known international authors, leading to the sorry neglect of equally talented Indian-language authors.

They have also formed strong bonds with college-going kids and young adults, who often hang about at Atta Galatta, to watch performances, to browse books or engage in conversations. “We encourage loitering,” says Subodh. They’ve even installed a ‘used books’ shelf to cater exclusively to browsers. Recently, at the Bangalore Literary Festival, the Atta Galatta outlet was manned primarily by volunteers. The Sankars realize that many millennials want to engage with literature and creative cultures, not necessarily as producers or even as patrons, but simply by offering their time to shelve books, pack boxes, or set up pop-up stores at festivals.

Though they’re not yet making profits, they often break even and find other means to finance themselves (Subodh engages in part-time consulting to fund their family expenses).

But in committing themselves to a new life and to new causes – bolstering Indian authors and artists, cultivating relationships with young volunteers and drop-ins, creating a space that champions cultural conversations – the Sankars have found a new freedom. After all, as the theologian Tim Keller puts it, freedom stems not from the absence of restraints, but in choosing the right ones.

References:

Brooks, David, The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life, Random House, New York, 2019

Brinda – This is one of the finest profiles I have read in recent times. I love your writing. Thanks for giving us a wonderful backstory of one of the finest couples in Bangalore!

I subscribe to the NYT just for David Brooks column, but somehow, I haven’t read the Second Mountain yet. Thanks for writing about it, this will be the next book I read.