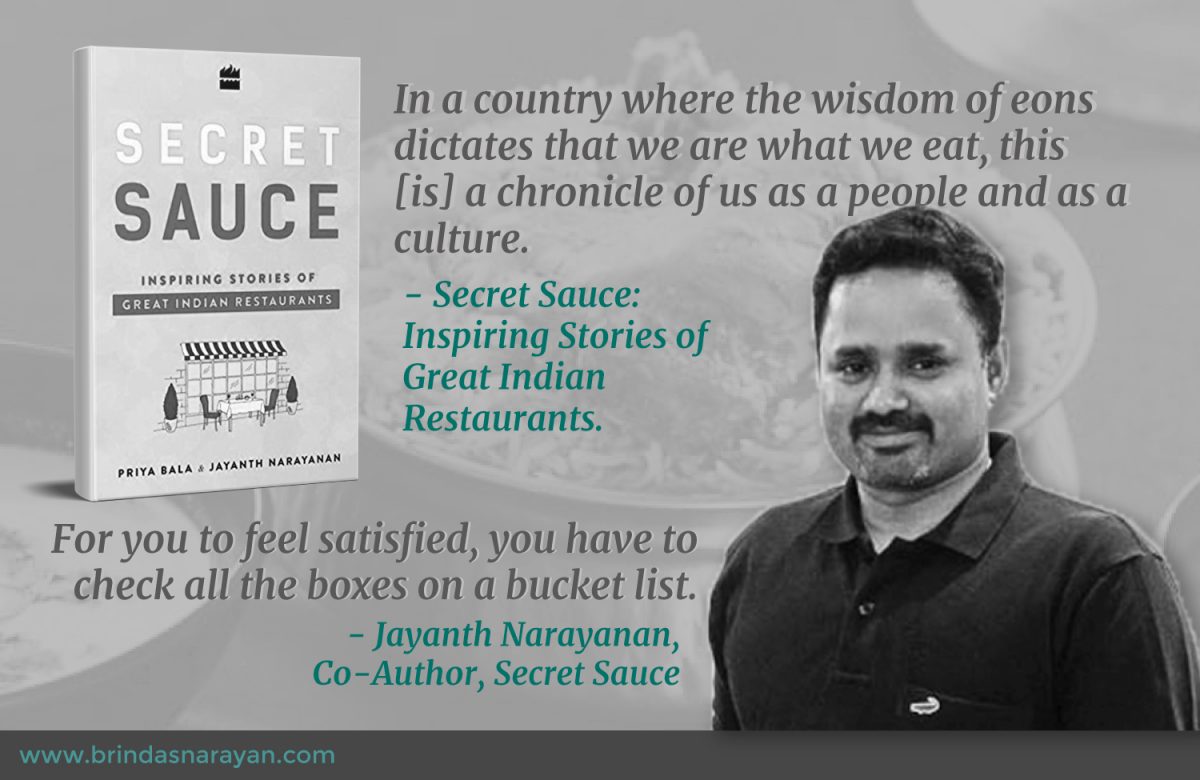

From a Techie to a Restaurateur, From a Blogger to a Co-Author: Lessons in Reinventing Yourself From Jayanth Narayanan

Jayanth Narayanan, Owner of Mani’s Dum Biryani and Co-author of Secret Sauce and Startup your Restaurant, Constantly Reinvents Himself

Mahatma Gandhi dwelt as intensely on the foods he and his followers consumed (or consciously avoided) as on larger political or spiritual themes. But he would have applauded the contemporary nation’s variegated palates as a hallmark of its receptiveness. Yet India, according to the authors of Secret Sauce, is a “punishing” market for most restaurateurs. However, a few iconic places have endured the vicissitudes of consumer fickleness. Jayanth Narayanan criss-crossed the country to chart the gripping stories of such gastronomic legends.

Like many of the vivid restaurant founders, Jayanth himself treaded an offbeat career path, transiting from selling technology to founding a restaurant, from blogging to co-authoring a popular series of food-business books. Emerging from a middle-class family in Chennai, Jayanth headed into an Engineering degree, fulfilling societal expectations to “do something practical.” While he cherished many aspects of his BITS Pilani experience, he wasn’t particularly drawn to his field of study. Instead of opting for an insipid job, he chose to acquire an MBA from XLRI. Soon after, he spent a few years in the U.S., selling technology products.

Even at college, he had always dreamt of starting his own business. Returning to India, he experimented with a BPO business, and then with a product company. Both enterprises, he acknowledges, did not take off. Besides, he had recently become a parent, and felt compelled to stabilize his finances. But after four-plus years at a job, when the urge to found his own enterprise resurfaced, he set up a health-food restaurant called “Café Aarogya.” “It was like an art movie,” reflects Jayanth wryly. “Critically applauded, but commercially unviable.”

For Aarogya, he had hired a chef named Mani, who suggested, when a decision to shut down the business was made, that they convert the “green” enterprise into a no-frills biryani outlet. Though Jayanth himself was vegetarian, he agreed with his employee that the business needed to align itself with customer appetites. Of course, the biryani was going to be cooked by Mani, whose distinctly South Indian name seemed like a comic foil to the dish. The outlet, zanily renamed “Mani’s Dum Biryani”, carted packages to customer homes before home-deliveries had become widespread.

Even as he steered his operation, Jayanth was always reflective about the mistakes he had made with his enterprise. Besides the menu, the location – off a main road, on the first floor of an unimpressive building – was not ideal. He watched other restaurants being set up on the same street, and then foreseeably collapse. He blogged about his insights, hoping to help other aspiring restaurateurs. When the posts started garnering consistently high hits, he wished to stitch the material into a book. But as an insightful and introspective person, he realized he couldn’t do this alone. He teamed up with Priya Bala, who was already a reputed restaurant critic and food writer.

After their first manuscript, Startup Your Restaurant was accepted by Harper Collins, the duo discovered that other restaurateurs in the nation had fascinating narratives. They pitched a second book to the publisher, and this time around, snagged a contract rather quickly. Secret Sauce offers rarely-documented snippets about restaurants that have forged our sense of nation as much as cricket and Bollywood.

Some Fascinating Snippets From Secret Sauce: Inspiring Stories of Great Indian Restaurants

Thirupati Raja of Adyar Anand Bhavan rises from penurious circumstances

In 1938, 10-year-old Raja ran away from his farmer family to work as a cleaner at a lunch home in Chennai. His fortune-seeking led him to Bombay, where he was ousted from his mill job when the factories shut down, then to Tamil Nadu, where his sugarcane farm was destroyed by a cyclone, to eventually establishing the sweet shop at Adyar in 1988. Since then, the business has mushroomed into the chain that dots cities, towns and highways across Karnataka and Tamil Nadu. But Raja’s tight controls of the cash box or “kalla petti” had been transmitted to the flourishing enterprise. Even while responding to the authors, Raja’s son refused to forsake his fiduciary duties, signing a six-inch stack of cheques while dwelling on the past.

Haji Karimuddin of Karim Restaurants imbibes the secrets of royal Mughal kitchens from his chef father.

Karim Restaurant, located in a narrow lane by Delhi’s Jama Masjid, recreates ancient Mughal recipes that were at one time the provenance only of royal kitchens. The founder’s father, Mohammad Awaiz, cooked for Bahadur Shah Jafar. When the emperor was ousted from his throne in 1857, Awaiz fled to Ghaziabad. However, he imparted his culinary secrets to his son, Haji Karimuddin. The Mughal emperors were fussy gourmets who insisted on tasty foods that were easy to digest. So Karimuddin imbibed the precise mix of spices, testing of ingredients, and other techniques that had once pleased the royals. Started as a small stall in 1911 to cater to the Delhi Durbar, an event to commemorate the crowning of George V, Karim has now expanded into a sprawling 300-seater.

Nelson Wang of China Garden invents the manchurian to wow Mumbai’s elites

Nelson Wang, was born to Chinese immigrants in Kolkata in 1950. He moved to Bombay in the 1970s, with just a suitcase and some cash. He started out as an assistant cook at a Chinese restaurant, and quickly grasped many of the operational basics. Later, when someone offered him a partnership at a hole-in-the-wall Chinese outlet, he grabbed it. The President of the Cricket Club of India loved the food at Wang’s modest eatery, and suggested he run a restaurant inside the Cricket Club’s premises. At the Club, Wang invented the chicken manchurian in response to a request from patrons, who said, “Kuch alag karo.” Winning over elites at the Club imbued him with the chutzpah to set up China Garden, which was “the dining place to be seen in, in the Mumbai of the ‘80s.” Soon Nelson both hosted many celebrities and was also invited to “Bollywood parties and glitzy Mumbai gatherings.”

The intrepid Ritu Dalmia learns invaluable lessons from failures and successes

The urbane Ritu Dalmia, founder of the much-talked about Diva in Delhi, gleaned valuable lessons from her first failure. When she started MezzaLuna in the 1990s, the Delhi crowd wasn’t ready for authentic Italian food yet. Undeterred, she shut shop in Delhi and built Vama in London. But nostalgia for her own country, brought her back to India in 1999, and the country had morphed significantly over the decade. Affluent customers now sought foods from all over the world. She started Diva in Greater Kailash, and soon won over critics and laypersons. Advice she proffers to other restaurateurs is that you “You must keep costs low” and “if it’s not working in six months, have the courage to cut your losses and get out.”

Yagnappa Maiya imports European restaurant practices into a South-Indian setting

In 1920, three brothers from the Maiya family migrated to Bangalore and were employed as cooks by affluent households. The oldest brother was persuaded to start a restaurant in 1924, which was then called the Brahmin Coffee Club. In 1951, Yagnappa, the middle brother, travelled to Europe to master best practices in restaurants. When he returned, he implemented best-in-class standards of service and hygiene. For instance, he ensured that the kitchen was completely hosed down twice a week and that all utensils and cutlery were sterilized. Before the advent of “see-through kitchens,” he permitted customers a glimpse of dosas glistening on steaming tavas. He also renamed the business, refashioning the Brahmin Coffee Club into the Mavalli Tiffin Room (MTR).

Jayanth Narayanan Deliberately Retains A Beginner’s Playfulness

With Mani’s Dum Biryani having grown into a well-functioning chain of 14 outlets spread across the city, Jayanth is satisfied about checking boxes on a bucket list. “For me starting a business, writing a book were two items on that list.” He adds that the books have hauled him out of the material rat race. Even as he and Priya embark on more books, he’s careful not to lose the lightheartedness of a novice: “Right now, I’m doing this without any expectations – the minute I take this seriously, I won’t enjoy it as much.”