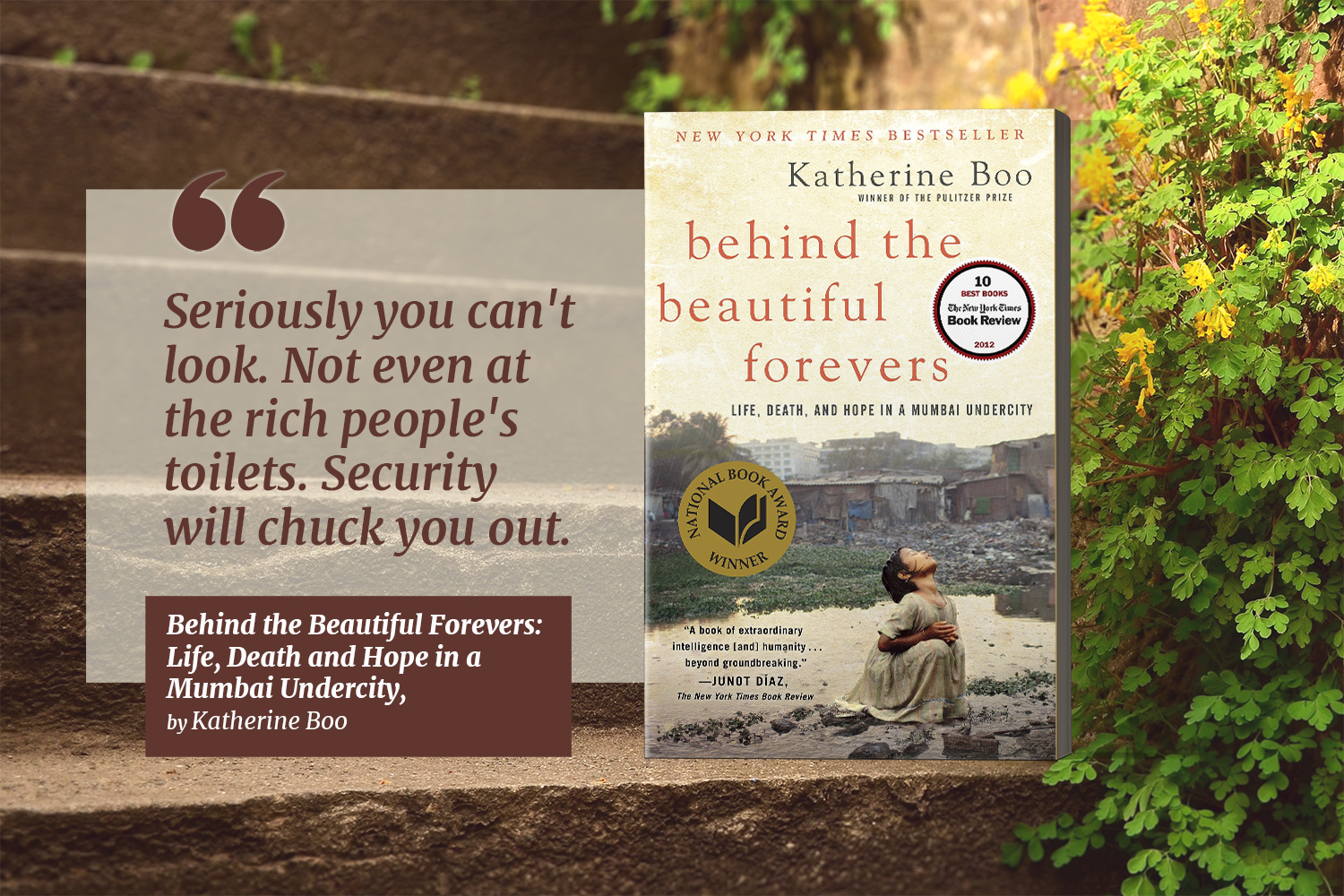

Lessons from Books: Turning Our Gaze from the Soaring Skylines to the Sordid Undercity

When driving out of Mumbai’s international airport, many upper-income Indians and foreign visitors may prefer to avert their gaze and look elsewhere. Anywhere else but at the sight that greets them at the Annawadi slum, where thousands are packed with a staggering density into a few hundred ramshackle huts.

But Katherine Boo was the kind of visitor who was unwilling to look away. Of course, as the wife of the Indian historian, Sunil Khilnani, she was already privy to the complex contours of the nation she was visiting. Beyond that she was a Pulitzer-winning investigative journalist, a writer who was tugged by the nuanced micro-stories that stitch up lives in the harshest of settings. With a frank alertness to the serendipities that braid personal and professional lives, in an online video, Boo says: “I wouldn’t have written this book if I hadn’t fallen in love with my husband Sunil.”

During her visits to post-liberalization India, Katherine couldn’t help but note the striking contrasts. On the one hand, steel-glass towers and luxury condominiums and five-star hotels were sprouting everywhere. On the other hand, the country continued to host millions of the teeming poor, who darted in and out of traffic stops and dwelt under zippy highways, their hardscrabble existence an ongoing rebuke to narratives of Progress. Even as she researched contemporary reports of the country, she could not find an adequate account of the manner in which the have-nots were negotiating such changes.

To document the stories that were obscured by the detritus of growth, she needed to position herself inside the right slum. For the first eight months, she moved from slum to slum inside Mumbai, trying to get a grip on the subcultures that distinguished one neighborhood from another. When she eventually settled on Annawadi, its discordant proximity to five luxury hotels did not escape Boo. In her book’s Prologue, she views the looming skyscrapers and glittery hotels from the bottomed-out view of the Annawadians: “It was a smogged-out, prosperity-driven obstacle course up there in the overcity, from which wads of possibility had tumbled down to the slums.”

At first, Boo herself, a blond woman in the midst of the “bedlam”, drew bewildered and astonished responses from the slumdwellers. Quite naturally, they thought she was misdirected or lost. In an interview with the NPR, she says, “I was a circus act. I was a freak. Everywhere I went, people would be like, ‘The Sheraton’, ‘The Hyatt’, ‘The Intercontinental’…” Eventually, since she ended up spending more than three years at the place, she was, like the best nonfiction writers, forgotten or treated like a wall-clock.

In her book, what strikes one as a reader, is the sheer inventiveness with which her characters deal with the ebbs and flows of their personal and family fortunes. Living on the edge of a sewage lake, which contains overspills from the airport and the surrounding towers, they plot small moves (or occasionally larger leaps) that can fuel their dreams: of Escape, of Other Lives, of Riches and Glamour, that are tantalizingly visible and yet impossibly distant.

For instance, there’s Abdul, the trash-sorter. He buys rubbish from rag-pickers, then sorts them out into saleable categories and sells them to local recyclers. All along, he seems to view his neighbors – all fellow-contenders in the Great Race to Nowhere Else – with a bemused and almost admirable detachment. He knows, as well, how small tilts in life can shake everything up. All it takes is an injury, or a slight, a policeman’s wrath or a landlord’s greed to dissolve his earnings or hopes.

As Katherine puts it, “A decent life was the train that hadn’t hit you, the slumlord you hadn’t offended, the malaria you hadn’t caught.” Inactions are as dexterously managed as actions. In the midst of all this, there is the difficulty or even impossibility, of staying on the right side of the law or of retaining, as Abdul miraculously does, a sense of morality.

One of the forms of Escape involves sniffing Eraz-ex – the white liquid that professionals use to blot out mistakes. Many of the young ragpickers are aware that the smells don’t stay on the rubbish, but accompany their small bodies, as they prize out plastic bottles, newspapers and metal scraps from the variegated heaps they scramble across. Trade in waste is a large contributor to the Annawadian economy. Of the 3000 residents that Katherine observes, during her time there, very few have reliable, salaried jobs. Most are construction workers, or maids, or ragpickers.

Boo’s stories compelling and pacy like a carefully constructed novel. Moreover, her language sparkles; and like any talented artist, she draws out the allure in the grotesque, the mélange of forms and shapes and colors in a pile of rot. But it’s the message that’s critical. Of a nation that perhaps, imperils itself, by ignoring the talents and flair and smarts of those who dwell by the “spangly blue haze by the sewage lake.” This book is illuminating, not only to global Indophiles like Boo, but to middle and upper-income Indians, who often pass by these slums without dwelling too much on the entangled lives inside.

References:

Boo, Katherine, Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity, Hamish Hamilton, Penguin, London, 2012.