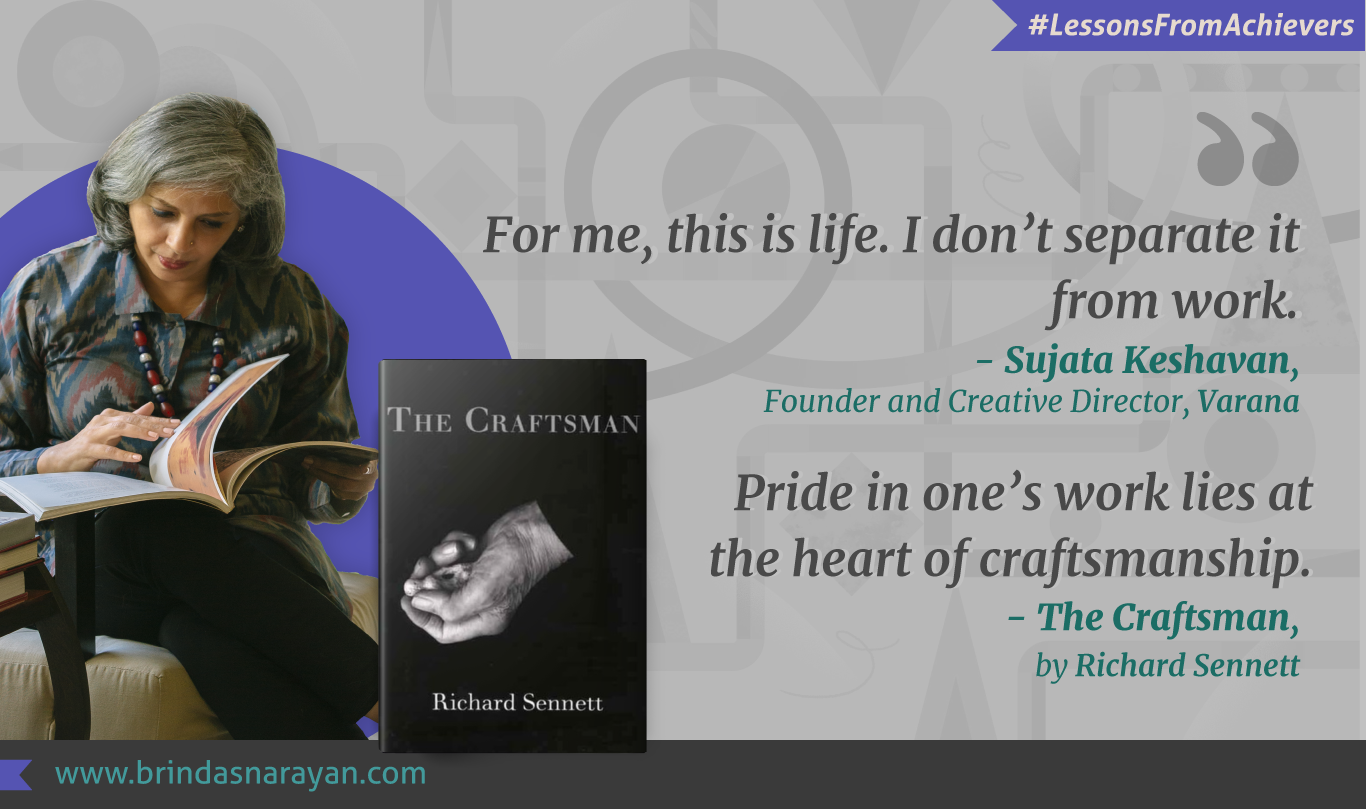

Sujata Keshavan, Founder and Creative Director, Varana and Founder, Ray+Keshavan, Chronicles her Incredible Journey

From The Craftsman: Sennett Expands The Notion of Craftsmanship

Pandora, the Goddess of Invention, was, according to the Greeks, not merely the giver of gifts. Opening Pandora’s jar or box was often considered a jeopardous act, one that could unleash not just creation, but also destruction. Curiosity and its fruits, in such legends, were treated as a danger. After all, Adam sinned when he bit into the apple of knowledge, wanting to know more than he, as a mere human, should have been satisfied with. Myths have always warned against trying to be too creative. After all, who are we, mere mortals, to play Gods?

Nonetheless, the human zeal to engage in Pandoric acts stays relentless, even as we remake and reshape the world, sometimes with breathtaking results and at other times, with catastrophic outcomes. In The Craftsman, the humanist-sociologist, Richard Sennett, is convinced that we can learn about ourselves through the objects we make. And his definition of a craftsperson is broader than we might think. According to Sennett, “craftsmanship” represents simply the “desire to do a job well for its own sake.” A craftsperson can be a programmer, doctor, teacher or even a parent.

In any craft, you establish a rhythm of problem solving and problem finding. During the Enlightenment, there was a belief that there is an “intelligent crafts[person]” in all of us. And knowhow to perform a particular craft does not merely reside in minds. As Sennett puts it, “All skills, even the most abstract, begin as bodily practices.”

Sujata Keshavan: Raised by Artistic and Offbeat Parents

Zealous pride in one’s work was threaded into the fabric of Sujata Keshavan’s life, across different strands. Hardly dwelling on the impossibility of what she was attempting, an intrepid Keshavan, still in her twenties, co-founded the eponymous design firm, Ray+Keshavan. She paid scant attention to the fact that in Delhi of the 1980s, pre-liberalization India was hardly geared up to support women founders, however ardent or audacious they might have been. Moreover, as one of the early pioneers in the rather nascent field of design, the climb was going to be steeper than for other enterprises. Rather than service an existing market, Keshavan had to spawn a new one, simultaneously educating customers about the rubrics of design even as she helped refashion their business narratives and brand aspirations.

The chutzpah to pursue such an offbeat path had perhaps been partially seeded by her parents. Her mother, Shanta Keshavan, was a painter, who had exhibited her abstract oils in Mumbai and Bangalore. Moreover, Shanta was a writer and an avid reader, drawn to eclectic and highbrow books in literature and philosophy. Her favorite author, Aldous Huxley, was as immersed in mysticism and philosophy as he was in stories and screenplays.

Besides painting, Shanta also dabbled in other Indian art forms. Modeling a capacity to be both playful and industrious, she also experimented with batiks. “She did different things at different stages,” Keshavan says. Sujata still recalls the large vats of batik dye, that were stored at the back of their house. Like in the charming scene in The Sound of Music, at a certain stage, both Keshavan and her sister frolicked in batik prints, as did the curtains fluttering on their windows.

Even as her artistic mother forged her own path when women were being hemmed in by rigid gender conventions, Sujata’s father also demonstrated an avant-garde , Do-It-Yourself mindset. Outside his professional activities at Burma Shell, he designed their house and all the furniture in it. Sujata and her historian husband, Ramachandra Guha, still occupy the home that her father conceived of and constructed. “It’s a small house, very compact, very timeless.”

Unsurprisingly then, a 10-year-old Keshavan was encouraged to pursue art lessons during her childhood in Bangalore. As a member of the Bangalore Art Club, run by the nationally-renowned sculptor and painter, Balan Nambiar, she attended art classes at Nambiar’s studio, where live models were captured on easels. For some sessions, Nambiar shepherded his young wards into the bamboo thickets and grassy sweeps of Cubbon Park, urging them to observe rocks and trees. Besides their hands-on immersion in figurative and natural forms, Keshavan and her sister were ushered into museums and galleries, where they encountered variegated takes on art.

From The Craftsman: The Acquisition of Hands-on Skills

As a future design professional, Keshavan had already fostered a discerning eye and imbibed hands-on artistic techniques. According to Sennett, skills in any craft are acquired by trained practice, by repetition, by doing. But paradoxically, how long you can practice also depends on what level of skill you have already attained. For instance, in violin playing, the Isaac Stern rule contends, that if you are more skilled in the violin, you can practice for longer without feeling the strain as much. As you become more skilled, what you practice also changes in nature.

But machines do pose obstacles to human beings acquiring skills. In earlier times, the machines substituted for repetitive physical tasks. Now, of course, machines are both enabling and threatening other spheres of our being.

For instance, in architecture, moving to CAD generated drawings removed the need to hand-draw or draft architectural designs. For some architects, this meant knowing the terrain less well, and also awarding less consideration to the effects of changes. In the hand-drawn era, architects were more intimately connected with the project. While the technology brings distinct advantages, it also takes away the physical engagement and repetitive tasks that were key to involvement and human learning.

Sujata Keshavan: Acquires a Top-notch Education in Design

Growing up largely in the pre-technology era, Sujata, like most academically-strong performers of that generation, pursued Science in her high-school years. Since she was also intensely drawn to Art, a degree in Fine Arts seemed like a possibility. But her father had also heard about the National Institute of Design (NID), and he felt like its combination of an aesthetic perspective married to industrial applications might be apt for her.

As it turned out, his hunch was spot on. After cracking the famously challenging entrance test to the Institute, Sujata reveled inside the program. While her aptitude for Art and Design was clearly demonstrable, she relished the manner in which Design ideals could be extended into different realms. She also recalls how NID, set up in 1961, was already more progressive than most Institutes of that time. When she entered the Ahmedabad campus in 1978 (after a harrowing three train rides from Bangalore), 50% of its admittees were women. Moreover, with faculty drawn from various parts of the world, the visionary five-and-half year program was imbued with a distinct point-of-view.

Although, she had initially set out to do Industrial Design, her exposure at NID sparked an interest in Textile Design. She learned how deep and ancient our country’s textile traditions were, and how past practices could be reignited with modern designs. Even as she absorbed the plethora of textile forms, she appreciated the painstaking labour and time involved in making a single warp.

Besides Textile Design, she was equally drawn to Graphic Design. Being more conceptual, the field demanded the constant begetting of new ideas. Such generativity had always been a part of her DNA and eventually, she opted to major in Graphic Design. With an exuberance that is rare among Indian college students, Sujata says: “I really loved every minute of my time there.”

On graduating from the program, she was itching to apply her facilities at work. Her first job, at the advertising firm, J Walter Thompson (JWT) exposed her to some of the pitfalls of an idealistic design approach in a terrain where customer sensibilities were yet to evolve. After six months at JWT, she joined the Deccan Herald, to design a new magazine with a fresh journalistic team. Soon after, marriage compelled her move to Calcutta, where she also met with Ram Ray, a likeminded advertising professional who was to partner with her later.

After a few months of freelancing at Calcutta, she was admitted to the prestigious Master’s in Design program at Yale University on a scholarship. Reputed as one of the strongest departments in Art and Design, the Yale program also drew Keshavan’s interest, because one of one its iconic faculty members. Paul Rand, also known as the “Father of Graphic Design,” elevated the status of designers by demonstrating how they were indispensable to building memorable business and institutional identities.

At her two-year program at Yale, Keshavan set higher standards for herself. She was keen on outdoing her own past work. Even as she learned the underpinnings of brand identities, she also soaked up different design slants and philosophies. Besides rigorous hands-on techniques, students were also encouraged to assimilate theory, including the History of Design and many other liberal arts courses inside the storied Ivy League.

After spending an extra year at Yale, working on projects, she returned to India with the intention to land an advertising job. But she realized soon enough that Indian advertising agencies didn’t understand and value design. So she chose to boldly chart her own path by creating her own design firm, perhaps unintentionally paving the way for many design firms that were to pop up later.

Initially established at Delhi, Keshavan was attentive to every aspect of the enterprise. She carefully picked her office furniture from Mini Boga of Taaru, who had leveraged Indian craft traditions to create sleek, minimalist pieces. It wasn’t just the space that was deliberately curated. The business was kickstarted on October 2nd, 1989, Mahatma Gandhi’s birthday – a fit beginning for a firm that was to shape some of the nation’s most iconic brands.

The firm’s first job was commissioned by a contemporary art gallery. That project, which encompassed many aspects of the gallery, started garnering attention straightaway: “What we did looked very different. I would still do it today.” Soon word started getting around. Visitors started asking who had created the posters and brochures. Leveraging on what is still one of the best methods to propagate one’s expertise – word-of-mouth – Ray+Keshavan started growing organically.

The enterprise had been forged just in time to capitalize on the 1991 liberalization of the Indian economy. Of course, Keshavan had to tide over many of the pitfalls of helming a business in a largely patriarchal setting. Contending with clients, some of whom were stereotypical, top-down, family-run businesses that did not settle dues on time, Keshavan also had to tolerate other irritants. For instance, the surrounding ecosystem was hardly geared up to service the fanatical attention to detail that Sujata sought.

Sensitized to the fact that a brilliant design concept would be degraded by poor execution, she personally monitored many aspects of the supply-chain. For instance, she visited printer sites to supervise printing jobs – and watch over nitty-gritties like the volume of inks used, the exact mélange of shades. She was so hands-on, that the printers tried to evade her hovering presence by scheduling her jobs at bizarre times like 1:30 a.m., knowing very well that Delhi was hardly a safe city for a woman to ride out at such hours.

An undeterred Sujata, who had befriended a few, trustworthy cab drivers, still traveled to the printing sites at Wazirpur. She recalls many late nights spent at such grungy facilities, with the men drinking inside cabins, while Keshavan stood obstinately outside – a lone woman who wasn’t going to give ground unless the quality met her high standards. To further dissuade her, some printers intentionally ran other jobs, hoping she would give in and leave: “I insisted on staying till my job was done. I was such a nuisance.”

From The Craftsman: Masters Struggle With Transmitting Tacit Knowledge

Keshavan’s drive to produce consistently high-quality materials was shared by many Master Craftsmen in medieval Europe. However, Sennett observes that we cannot completely subscribe to the romanticized notion of the medieval workshop, where only peace and harmony prevailed. There were, like even in modern workplaces, the conflicting tugs of autonomy and authority. While thinkers like Karl Marx and Charles Fourier tended to idealize the workshop, but it wasn’t always such an idyllic space. The manner in which knowledge was transmitted by the master craftsperson also depended on the chemistry between the master and learners.

The workshops in Europe also derived their sanctity from the fact that they were thought to be run on Christian principles. Craftspersons were valued too, because Christ himself was the son of a carpenter. Even inside monasteries, like inside the Saint Gall in Switzerland, monks gardened, practiced carpentry and grew herbs.

Often, despite students actively imitating and watching the master, certain craft practices are difficult to transmit. A case in point involves the making of Stradivari violins, where the master craftsman, Antonio Stradivari was closely involved in the process, and would appear at any point, to exhort his pupils to do this or that, throwing tantrums and issuing commands. He also decided to sell his violins in the open market, creating a singular reputation (brand) for himself. Later, when his sons inherited the business and tried to replicate their father’s violins, somehow the end-product always fell short of the instruments created by the renowned, incredibly talented Master.

Sujata Keshavan: Ray+Keshavan Makes Strides in a Growing Nation

Unlike Stradivari, Keshavan consciously diffused her methods among her team members.

As Ray+Keshavan continued to grow, with new clients attracted to their cerebral and hip designs, new design businesses started sprouting in the Indian market. As an offshoot, Keshavan started finding more skilled talent.

In the meanwhile, since she had young children, and she and her husband preferred to raise them in Bangalore, they moved to the South. As it turned out, that decision was a fortuitous one, because Ray+Keshavan caught the headwinds of the new economy. The firm grew along with the mushrooming IT and dotcom sectors. Many employees also shifted from Delhi to the new Bangalore headquarters. Some of their marquee assignments during this period included reshaping the brand image of the Escorts Group as well as architecting the Infosys brand.

As more Indian companies wished to explore foreign markets for their products and services, Keshavan was a natural cultural bridge. Already intimate with Indian cultural nuances, she was also attuned to the design sensibilities of Western consumers.

All along, she continued to educate customers about what design entailed. Her own firm approached each project with an intensity and depth that even her clients hadn’t envisioned. They interviewed existing users, users who had abandoned the product and service, and employees, garnering an insider/outsider perspective of the client’s business that hadn’t been offered up till then.

Terming their offering “strategic design” to encompass the manner in which the team entrenched itself in every aspect of the business before proposing a particular narrative and aesthetic, Sujata insisted on presenting her findings to Board Members. She knew that some of the broader changes she was engendering could not be approved or even appreciated by Marketing Managers. She also trained her own employees not to dive into the design requirements before acquiring such an immersive understanding.

During this phase, they also worked with several airports, with the partially Tata-owned airline, Vistara, and with one of India’s largest, homegrown financial institutions, Kotak. With projects that crisscrossed many sectors, their team learned to interact with a broad cross-section of people. One of their more enduring brand transformations was with a company that operated in the traditional Ayurvedic sector. Himalaya Healthcare had, at that point, about 150 different products, but none looked like each other. “There were different medicines, with different names and different designs.” Keshavan worked closely with the company for two years to completely transform its image. The person she worked with at Himalaya is currently her business partner in her latest venture.

As Ray+Keshavan continued to thrive, Sujata started feeling like her own work was getting repetitive. Besides, she could no longer get into the hands-on, micro-details, as she had to attend to larger macro-issues. Ready to personally move on to something else, she started considering offers from interested buyers. The firm had already received many potential buy offers, from the year 2000. But finding a partner with a synergistic outlook wasn’t easy. So Keshavan stalled the sale till 2006, when she sold 51% of the stake to the British advertising firm, WPP. Staying to steer the business till 2014, she sold 10% more each year.

From The Craftsman: Denis Diderot Creates The Encyclopedia

As Ray+Keshavan had demonstrated with various projects, powerful graphic designs can transcend mere textual descriptions. Denis Diderot was to discover this in a rather visceral manner, when working on The Encyclopedia.

Diderot was a poor provincial who migrated to Paris and ran into debt. He started working on The Encyclopedia or Dictionary of Arts and Crafts to stave off his creditors. One of the key things The Encyclopedia did was to value manual labor as much as mental tasks and to dismiss the worth of the hereditary elite. The book, widely read by everyone from Catherine the Great in Russia to merchants in New York, celebrated those who did work well for its own sake.

The Encyclopedia valued the contributions of a striving worker more than her rich and bored employer – in one particularly telling plate, a maid doing up her mistress’ hair radiates more energy and purpose than the bored mistress.

In trying to capture how people made things, Diderot confronted the limits of language. Besides, most craftspersons struggled to explain their ways of doing in words. This, however, did not mean they were stupid or bad at their jobs.

There were times too, when Diderot also tried to get his hands dirty and actually do the work in order to understand it better. But of course, he could not become an overnight master, and hence could never understand what it felt like when one’s practice was deeply embedded into one’s brain and body.

Diderot partially overcame this obstacle by using images – visual pictures – to communicate the decisive steps by which a task was completed. In Zen Buddhist practices too, Sennett notes, contemplation and silence is encouraged, and hence showing is elevated over telling.

Sujata Keshavan: Embarks on a New Venture

In the meanwhile, Sujata was keen on testing her own bodily and cognitive skills in a new arena. She had noted that India hadn’t created any distinctive global B2C brands. All the IT companies were B2B brands, and Jaguar, bought by TATA, hadn’t been forged from scratch by an Indian company. Wondering why Indian companies hadn’t forayed into consumer segments, she discussed the void with Ravi Prasad of Himalaya Healthcare, her ex-client. She also recalled her own time at NID, when she had been fascinated by the nation’s deep textile traditions and fabulous textile weaves. She strongly felt that an Indian company could make a dent in Western markets, if the expertise and skills of our craftspersons were appropriately showcased. By then, Prasad had also moved on from Himalaya, so he decided to partner with her in this new enterprise.

By retailing their products at high-end places like at Dover Street in London, Varana (https://varana.com/) works with expert craftspersons, who are encouraged and even prodded to reach new heights of performance. So far, because of cost constraints, most craftspersons could not afford to do their best work. But by retailing at the high-end, Varana is according such traditions with the value and patience they deserve. “Each piece is beautifully made,” says Keshavan. “No one has looked at Khadi like this before.”

Pouring all her energies into this project, Keshavan has also invested intensely in textile research to ensure impeccable finishes. Moreover, with their designs bridging the gap between traditional crafts and contemporary consumer styles, Varana is poised to make a mark in high-street global fashion. Besides the immensely finespun clothing lines, Varana is also fashioning a high-end Ayurvedic brand, Almora. Forging 100% natural products that have been rigorously tested by dermatologists, the business aims to bring other aspects of Indian traditional know-how within the reach of Western consumers.

From The Craftsman: Becoming One with One’s Craft Practice

At this point, Keshavan herself is working as zealously and passionately as she always has been, investing “every waking moment” into the new enterprise, with a focus that ripples down to the craftspersons engaged by her business.

You cannot get emotionally or intellectually engaged in a task or subject, until you are able to focus. So the ability to pay attention has to be developed first. You reach a state, which the philosopher Maurice Merleau Ponty describes as “being as a thing.” According to Sennett, we are now so absorbed in an activity, that we are no longer aware of our bodily self. “We have become the thing on which we are working.”

Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman, Penguin Books, London, 2009.